DeepGreen closer to mining battery metals from the sea after $150m injection

The financing, provided by Switzerland-based offshore pipeline company Allseas Group, is a welcome sign of progress for the deep sea mining sector, which has been stalled due regulatory uncertainty and environmental concerns.

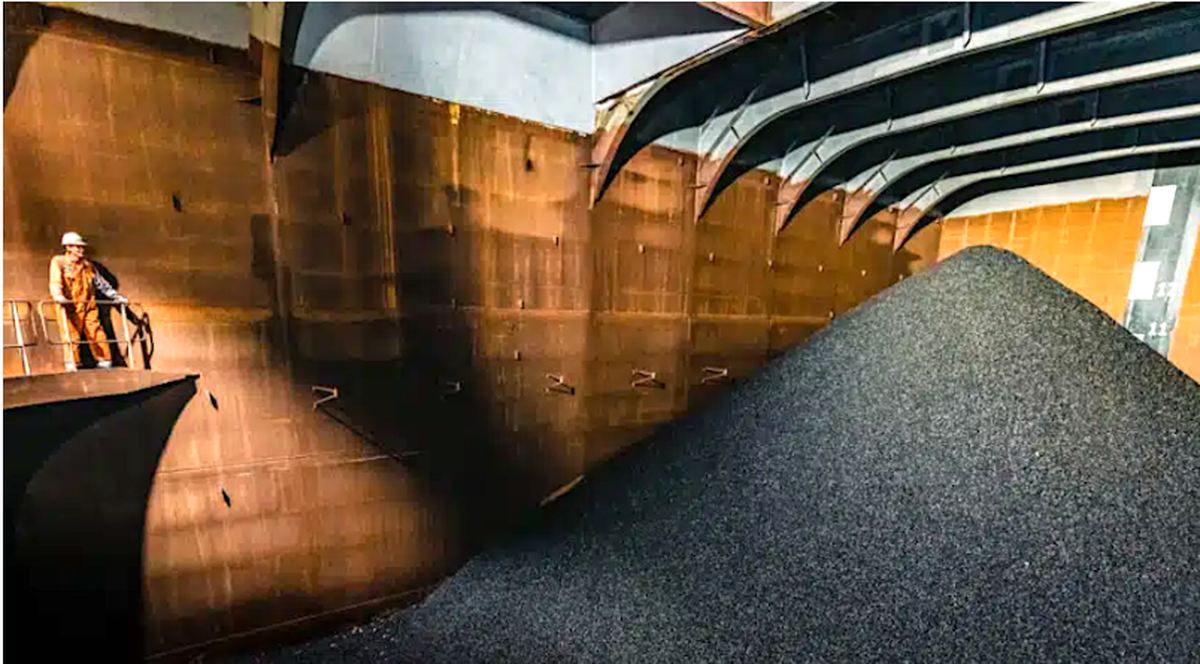

Unlike other seafloor mining companies, including pioneer Nautilus Minerals, the Vancouver-based explorer doesn’t want to drill, blast or dig the bottom of the ocean. DeepGreen’s main goal is to scoop up small metallic rocks located thousands of metres below the surface in the North Pacific Ocean.

Unlike other seafloor mining companies, the Canadian start-up doesn’t want to drill, blast or dig the bottom of the ocean, but to scoop up small rocks containing cobalt, nickel and other battery metals.

Its exploration focus is the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a mineral-rich, 4,000-kilometre swath of the Pacific that stretches from Hawaii to Mexico, where billions of potato-sized metals-rich rocks lie in a shallow layer of mud on the seafloor.

The deep sea, more than half the world’s surface, contains more cobalt, nickel, copper, manganese and rare earth metals than all land reserves combined, according to the US Geological Survey.

Companies exploring or already developing projects to mine the seafloor argue the extraction of those deep-buried riches could help diversify the sources currently supplying metals needed for electronics and evolving green technologies, such as electric vehicles (EVs) and solar panels.

Academics and scientist, however, are concerned by the lack of research on the possible impacts of high seas mining. They fear the activity could devastate fragile ecosystems that are slow to recover in the highly pressurized darkness of the deep sea, as well as having knock-on effects on the wider ocean environment.

Not enough studies

Last year, the European Parliament called for a ban on seabed mining until the environmental impacts and risks of disturbing unique deep-sea ecosystems are understood. In the resolution, it also urged the European Commission to persuade member states to stop sponsoring and subsidizing licenses to explore and exploit the seabed in international waters as well as within their own territories.

Shortly after, an international team of researchers published a set of criteria to help the International Seabed Authority (ISA), a UN body made up of 168 countries, protect biodiversity from deep-sea mining activities.

So far, it has granted 29 licences to governments and companies, authorizing them to explore in international waters.

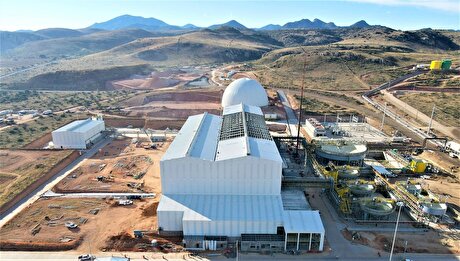

Nautilus, however, is the only company that has gone beyond the exploration stage and has gotten close to open the first polymetallic seabed mine off the coast of Papua New Guinea. Its Solwara 1 project, however, has been slowed by funding issues and local opposition.

Anglo American (LON:AAL) sold its 4% stake in Nautilus a year ago, as part of efforts to retain only its most profitable assets. And, in March, it had to delist from the Toronto Stock Exchange.

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Trump weighs using $2 billion in CHIPS Act funding for critical minerals

Pan American locks in $2.1B takeover of MAG Silver

Codelco cuts 2025 copper forecast after El Teniente mine collapse

SQM boosts lithium supply plans as prices flick higher

US adds copper, potash, silicon in critical minerals list shake-up

Viridis unveils 200Mt initial reserve for Brazil rare earth project

Gold price gains 1% as Powell gives dovish signal

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

KoBold Metals granted lithium exploration rights in Congo

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Silver price touches $39 as market weighs rate cut outlook