Scientists take a look inside rare wire gold specimen

Using neutron characterization techniques, the researchers were able to take a look to try to better understand how the shiny object was formed.

"Almost nothing other than the existence of the specimen is known about wire gold," said Sven Vogel, a physicist at Los Alamos National Laboratory's neutron science center.

According to Vogel, wire silver is more common in nature but its yellow counterpart is so rare that this particular specimen is almost invaluable.

"Wire silver is a mosaic-like polycrystalline aggregate with many hundreds to thousands of crystals in a single wire," explained John Rakovan, Professor of Mineralogy at Miami University and one of the researchers involved in the experiment. "The gold appears to be composed of only a few single crystals. Furthermore, we discovered that these samples are not pure gold, but rather gold-silver alloys with as much as 30 percent silver substituting for gold in the atomic structure."

Using the lab's neutron source, which is normally utilized to study materials like uranium alloys or nuclear fuels, the experts were able to verify that this sample is homogeneous, meaning the whole sample is a 70-30 mix of gold to silver.

In their view, this could mean that the silver is bonding to the gold in the crystalline structure at the atomistic level.

"The results of this study will have implications for geoscientists who are trying to understand the geochemical processes that are at play in the formation of gold deposits, and for materials scientists and engineers who may use the unique properties of these materials in technological applications," the scientists said in a media statement.

The Ram's Horn belongs to the collection of the Mineralogical and Geological Museum at Harvard University and it was initially found in 1887 at the Ground Hog mine in Red Cliff, Colorado.

According to the museum curators, the mysteriously shaped artifact that resembles a twisted bunch of wires and not the usual golden nugget has baffled mineralogists since its discovery.

Gold price edges up as market awaits Fed minutes, Powell speech

Glencore trader who led ill-fated battery recycling push to exit

Emirates Global Aluminium unit to exit Guinea after mine seized

UBS lifts 2026 gold forecasts on US macro risks

Iron ore price dips on China blast furnace cuts, US trade restrictions

Roshel, Swebor partner to produce ballistic-grade steel in Canada

US hikes steel, aluminum tariffs on imported wind turbines, cranes, railcars

EverMetal launches US-based critical metals recycling platform

Afghanistan says China seeks its participation in Belt and Road Initiative

First Quantum drops plan to sell stakes in Zambia copper mines

Ivanhoe advances Kamoa dewatering plan, plans forecasts

Texas factory gives Chinese copper firm an edge in tariff war

Pan American locks in $2.1B takeover of MAG Silver

Iron ore prices hit one-week high after fatal incident halts Rio Tinto’s Simandou project

US adds copper, potash, silicon in critical minerals list shake-up

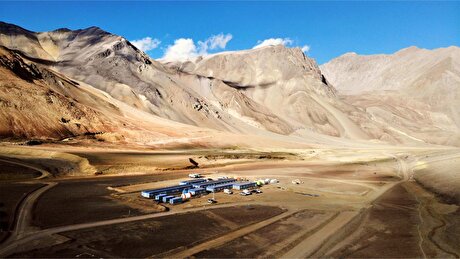

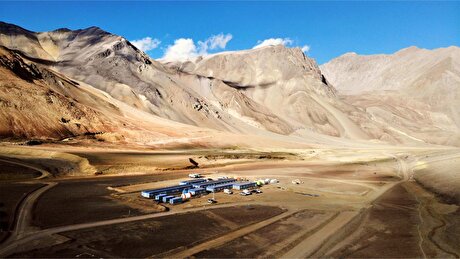

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Gold price gains 1% as Powell gives dovish signal

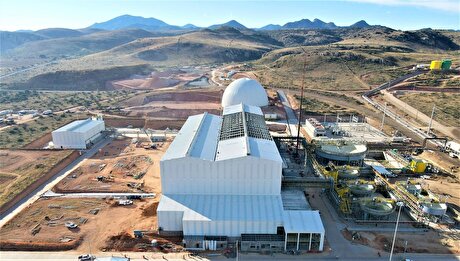

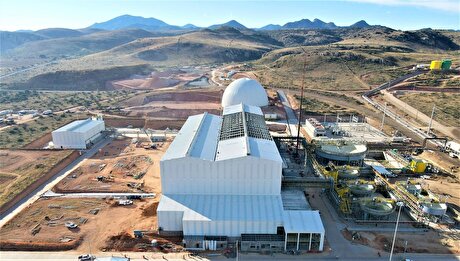

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Gold boom drives rising costs for Aussie producers

First Quantum drops plan to sell stakes in Zambia copper mines

Ivanhoe advances Kamoa dewatering plan, plans forecasts

Texas factory gives Chinese copper firm an edge in tariff war

Pan American locks in $2.1B takeover of MAG Silver

Iron ore prices hit one-week high after fatal incident halts Rio Tinto’s Simandou project

US adds copper, potash, silicon in critical minerals list shake-up

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Gold price gains 1% as Powell gives dovish signal

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery