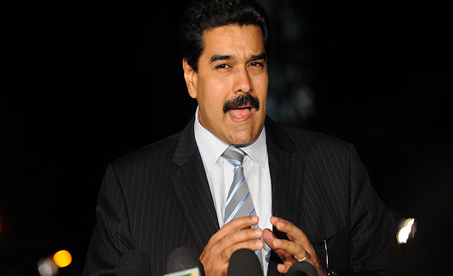

In Maduro's Venezuela, even counting gold bars is a challenge

The answer has taken on added significance as beleaguered President Nicolas Maduro faces increasing pressure to resign. Last week, countries including the U.S. and U.K. recognized the leader of the National Assembly, Juan Guaido, as the Venezuela’s legitimate leader, amid mass protests. On Monday, the Trump administration issued new sanctions that effectively block crude exports to the U.S., where Venezuela gets the bulk of its cash.

While crude is by far Venezuela’s largest export, refined oil and then gold both make up significant sources of revenue, according to data compiled by the Observatory of Economic Complexity of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But both the nation’s gold reserves and mining production have dropped in recent years as Maduro’s regime used the yellow metal to generate hard currency in international transactions — and even to exchange it for food and medicine.

Venezuela’s foreign reserves — 76 percent of which are held in gold, according to the World Gold Council — have fallen 69 percent to $8.4 billion since Maduro came to power in April 2013 following the death of President Hugo Chavez, according to central bank data. With no detailed or reliable national reports, it’s difficult to know where that gold is going.

Mysterious transactions

Venezuela used to export gold to Switzerland, but it hasn’t done so for the past two years, according to Caracas Capital Markets managing partner Russ Dallen, citing Swiss trade data. Dallen, who has tracked investments and gold in Venezuela for almost three decades, says Maduro’s regime exported gold valued at just over $2 billion in the past two years — $1.1 billion to the United Arab Emirates in December 2017 and $901 million to Turkey in the first 10 months of 2018.

Other transactions remain a mystery. Venezuela’s gold holdings decreased to $5.45 billion in November last year, from $6.12 billion the previous month, and the missing $700 million hasn’t come up on trade data for Switzerland or Turkey, Dallen said. Whether the gold came from the central bank’s existing holdings, or was new output from the country’s mines, is another unanswered question.

‘Difficult’ to know

“We think that most of what got into Turkey last year came from mining operations,” Dallen said. “But it’s difficult for us to know.”

The Bank of England holds about $1.2 billion worth of gold for Venezuela; the Maduro regime has been trying to retrieve that gold for weeks. But it’s unclear how much gold may be in the resource-rich Latin American country.

Independent observers haven’t been able to access the central bank’s vault for years. The last non-government official to physically see the reserves is thought to be Francisco Rodriguez, now chief economist at Torino Capital. In 2014, he took a peek at the reserves and said he saw the estimated $15 billion in gold bars — which fit into “five small cells that were not even full to the top.”

20 tons

On Tuesday, a tweet by Venezuelan lawmaker Jose Guerra set off social media speculation and outrage. A Russian Boeing 777 had landed in Caracas the previous day to spirit away 20 tons of gold from the vaults of the central bank, Guerra said, without providing any evidence. Separately, a person with direct knowledge of the matter told Bloomberg News that 20 tons of gold have been set aside in the central bank for loading. Worth some $840 million, the gold represents about 20 percent of its holdings of the metal in Venezuela, the person said.

As for gold production, the country’s once vibrant exploration activity plummeted after Chavez came to power in 1999 and nationalized foreign companies’ mining licenses and assets. While gold production increased 76 percent from 1999 through 2005, output only grew 3 percent from 2006 through 2011, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, which stopped receiving official data from Venezuelan production in 2004.

Arco Minero

The World Gold Council’s latest report says Venezuelan gold production has been decreasing since 2011, when the country produced 25.5 tons. In 2017, the Council puts output at 23 tons. A lot of the gold is mined in the Arco Minero del Orinoco region, a stretch of jungle spanning 70,000 square miles from Colombia to Guyana.

Maduro’s government claims that the area holds as much as 8,000 tons of gold, which would make it one of the world’s largest deposits. The region produced 8.5 tons in 2017, the government said in April. While production is controlled by the army, gold is extracted in artisanal mines in very poor conditions. The region’s main town, El Callao, was ranked as the country’s most-violent municipality in 2017.

In the event of a regime change, whatever gold is left in the central bank’s possession will be important because it could be used as collateral for the loans the country will need to rebuild its economy, said Oren Barack, managing director of fixed income at AGP Alliance Global Partners.

But for Venezuela, the resources that have already been extracted may matter less than what’s still untouched, Dallen said.

“Even if the vault was empty, the oil, gold and natural gas reserves remain underground,” he says. “That’s what bondholders and the IMF are counting on for the future.”

Gold price edges up as market awaits Fed minutes, Powell speech

Glencore trader who led ill-fated battery recycling push to exit

Emirates Global Aluminium unit to exit Guinea after mine seized

UBS lifts 2026 gold forecasts on US macro risks

Iron ore price dips on China blast furnace cuts, US trade restrictions

Roshel, Swebor partner to produce ballistic-grade steel in Canada

US hikes steel, aluminum tariffs on imported wind turbines, cranes, railcars

EverMetal launches US-based critical metals recycling platform

Afghanistan says China seeks its participation in Belt and Road Initiative

First Quantum drops plan to sell stakes in Zambia copper mines

Ivanhoe advances Kamoa dewatering plan, plans forecasts

Texas factory gives Chinese copper firm an edge in tariff war

Pan American locks in $2.1B takeover of MAG Silver

Iron ore prices hit one-week high after fatal incident halts Rio Tinto’s Simandou project

US adds copper, potash, silicon in critical minerals list shake-up

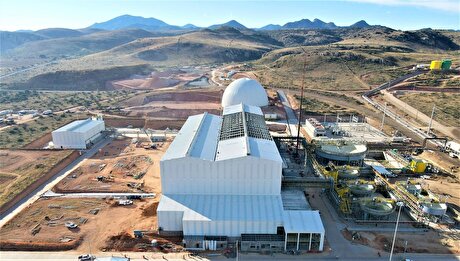

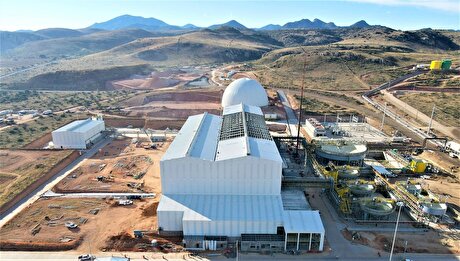

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Gold price gains 1% as Powell gives dovish signal

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Gold boom drives rising costs for Aussie producers

First Quantum drops plan to sell stakes in Zambia copper mines

Ivanhoe advances Kamoa dewatering plan, plans forecasts

Texas factory gives Chinese copper firm an edge in tariff war

Pan American locks in $2.1B takeover of MAG Silver

Iron ore prices hit one-week high after fatal incident halts Rio Tinto’s Simandou project

US adds copper, potash, silicon in critical minerals list shake-up

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Gold price gains 1% as Powell gives dovish signal

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery