Virus-hit China may need more imports of coal. The tricky part – shipping it there: Clyde Russell

While there may be increased demand for imported coal in China in coming weeks, the problem for major exporters such as Indonesia, Australia and the United States is going to be one of logistics.

The coronavirus is starting to have an impact on supply chains and will make it more challenging for shippers to find vessels to go to China. And even if exporters do get their goods to Chinese ports, they will likely face headaches in unloading cargoes and transporting them from docks to end-users.

By Thursday, the country’s health authority said, the death toll from the coronavirus outbreak that started in the Chinese city of Wuhan had reached 563, with more than 28,000 others infected.

While the fatalities and infections draw headlines, the impact of the virus is starting to cascade through China’s economy – as well as businesses in countries that trade heavily with the world’s largest consumer of commodities.

The challenge of shipping coal to China was illustrated by the Australian government’s decision to impose a 14-day quarantine on vessels leaving mainland China after Feb. 1.

The rate to ship coal from Newcastle to China dropped to $5.87 a tonne on Wednesday, the lowest in almost four years

This means such vessels will face delays upon reaching Australian ports, as the sailing time between China and both the east and west coasts of Australia is generally less than 14 days.

Vessel queues outside Australian coal ports are already lengthening. Argus Media reported on Feb. 4 that the number of ships waiting outside Newcastle, the world’s largest coal export harbor, was at an 18-month high of 20 vessels.

There are some other factors that may be contributing to longer vessel waiting times, such as weather and port and rail maintenance, but the overall trend is clear: Shipments to, as well as from, China are becoming more complicated to arrange.

Freight rates plunge

At these freight prices, shipping companies will be losing money on every voyage, while they are also facing higher costs from the mandatory switch to cleaner fuels that kicked in last month as part of a change in global shipping regulations known as IMO2020.

While the cost of shipping may be depressed, the main challenge will be securing vessels with owners prepared to send them to China.

Certainly, Asian seaborne coal prices have yet to show any meaningful spike from China’s domestic coal woes.

The price of 6,000 kilocalorie per kilogram (kcal/kg) coal at Newcastle, as assessed by brokers Tullett Prebon climbed to $69.35 a tonne on Thursday, up from a recent low of $66.30 on Feb. 3, but still below the high so far this year of $72 on Jan. 13.

The price of lower-quality 4,200 kcal/kg coal from Indonesia has fared better, with the weekly Argus index rising to a six-month high of $35.48 a tonne in the week ended Jan. 31.

The rise in the Indonesian coal price follows similar gains in domestic prices in China, with thermal coal at Qinhuangdao, as assessed by SteelHome ending at 563 yuan ($80.66) on Wednesday, down slightly from 564 yuan on Feb. 4, which was the highest in three months.

The coal market appears to be reacting with caution to the coronavirus, with still considerable uncertainty over how much domestic output has been lost, what transport bottlenecks exist currently in China and whether more imported coal will be needed. Even if it is, can it get there efficiently?

What is becoming clearer is that the efforts to contain the virus by limiting economic activity in China is going to have multiple flow-on effects through commodity supply chains.

Hindustan Zinc to invest $438 million to build reprocessing plant

Gold price edges up as market awaits Fed minutes, Powell speech

Glencore trader who led ill-fated battery recycling push to exit

UBS lifts 2026 gold forecasts on US macro risks

Roshel, Swebor partner to produce ballistic-grade steel in Canada

Iron ore price dips on China blast furnace cuts, US trade restrictions

EverMetal launches US-based critical metals recycling platform

South Africa mining lobby gives draft law feedback with concerns

US hikes steel, aluminum tariffs on imported wind turbines, cranes, railcars

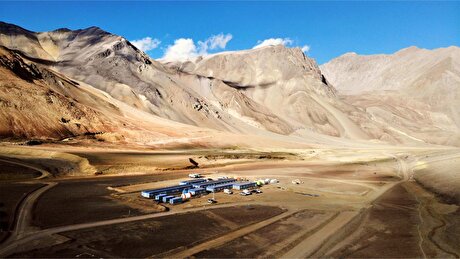

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Gold price gains 1% as Powell gives dovish signal

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Gold boom drives rising costs for Aussie producers

Vulcan Elements enters US rare earth magnet manufacturing race

Trump raises stakes over Resolution Copper project with BHP, Rio Tinto CEOs at White House

US seeks to stockpile cobalt for first time in decades

Trump weighs using $2 billion in CHIPS Act funding for critical minerals

Nevada army depot to serve as base for first US strategic minerals stockpile

Emirates Global Aluminium unit to exit Guinea after mine seized

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Gold price gains 1% as Powell gives dovish signal

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Gold boom drives rising costs for Aussie producers

Vulcan Elements enters US rare earth magnet manufacturing race

US seeks to stockpile cobalt for first time in decades

Trump weighs using $2 billion in CHIPS Act funding for critical minerals

Nevada army depot to serve as base for first US strategic minerals stockpile

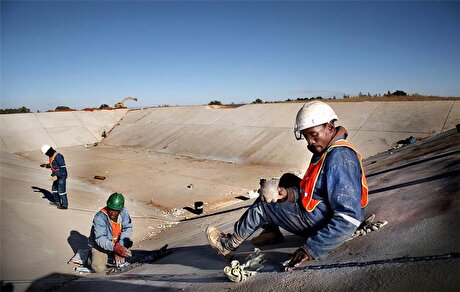

Tailings could meet much of US critical mineral demand – study