Q&A: UK Oftec recommends biofuels for off-grid heating

The RHI ends in 2021 and government is currently considering how to incentivise the deployment of renewable heat beyond that date. A key reason for the low uptake of the RHI scheme is because the technologies it supports are very expensive and, in the case of electric heat pumps, because they are difficult to retrofit into older buildings. If cost and household disruption is high, consumers will be unable or unwilling to support low carbon technologies and efforts to reduce emissions could fail.

We think the government should concentrate on supporting fabric improvements to buildings first, while creating a marketplace for viable renewable heating technologies that delivers competition and choice for consumers — which we think should include low-carbon liquid fuels. This will encourage solutions that will cope with a range of locations and build scenarios, and allow for evolution in technology and technical development.

How does this align itself with the current supply of biofuels to the UK?

The fuel we plan to introduce by 2027 will contain a 30pc blend of Fame biodiesel with kerosine. Fame has excellent availability and the price is moving closer to kerosine. We first need to build on previous field testing but we are confident this could be an attractive and technically straightforward solution that consumers will welcome. Currently, around 3mn t of kerosine is used each year for heating. However, research we have commissioned suggests there is potential to reduce consumption by around a third if the government makes a serious commitment to delivering energy efficiency support, which off-grid homes desperately need — 97pc are currently in EPC bands D-G.

Assuming this happens, and that some easy-to-convert homes switch to heat pumps, we anticipate that Fame demand will be around two-thirds of 1mn t. Beyond that, the plan is to move to a 100pc low-carbon fuel. This is also likely to be a blended fuel, utilising options such as Fame, hydrotreated vegetable oil and pyrolysis oils.

We are working with academia and will use our forthcoming field trials to assess and test the performance of a range of blend options. Future availability will also be a factor, so we will be looking closely at developments in other sectors such as aviation.

What costs will be incurred in terms of upgrading heating oil infrastructure and are there associated issues with the cold-weather properties of biodiesel, such as cloud point?

We are working with others in the supply chain, including UKIFDA and TSA, to assess what the impact will be, and what changes will be required. There's now a lot of knowledge available around the storage and handling of Fame which we will augment with our own trials to ensure any issues are managed appropriately.

To what extent must associated legislation incentivise the uptake of liquid biofuels in the heating oil sector, given transport incentives under the Renewable Transport Fuels Obligation (RTFO)?

A similar obligation-style arrangement for the heating sector would help to provide investor confidence and certainty for consumers around future heating choice. A short-term feed-in support may also be necessary to enable a smooth transition. However, a programme of cost-effective energy efficiency improvements, funded by government, covering both fabric upgrades and the replacement of the most inefficient boilers and oldest tanks, would reduce most household bills significantly — more than absorbing any increase in fuel price.

In terms of feedstock, should UK legislation for bio-based liquid heating oil encourage a greater share of waste and should there be a similar "crop cap" to that implemented to 2032 under the RTFO?

To ensure the sustainability attributes of the fuel, we strongly favour wastes such as used cooking oil as the primary feedstock, although small amounts of product with a low risk of indirect land use change may also be used. We will certainly be pressing government to expand UK waste capture and processing capacity, and to support initiatives across Europe and elsewhere.

Heating appliances are more efficient than transport applications, so in terms of the hierarchy of use, it makes more sense to prioritise biofuels for heating. However, such issues may not arise. Department for Transport (DfT) projections show that as electric vehicle deployment gathers pace during the 2020s, so the demand for biodiesel will decline, leading to a potential glut in supply.

What are the associated pricing constraints to the implementation of such a policy, given the premium for waste-based biofuels over those produced from crops, both for conventional biodiesel and hydrotreated vegetable oil?

It's widely accepted that as we move to a low-carbon economy, the cost of the energy we use may rise, at least in the short term. However, the use of waste-derived product is vital to satisfy legitimate environmental concerns. That's why reducing demand is important and why we favour an energy efficiency retrofit programme in parallel with a fuel change.

The biggest hurdle for consumers is capital costs. Alternative heating options such as electrification place such a high capital burden on households that they risk alienating support for decarbonisation, potentially derailing progress when we need to accelerate it. In many cases, switching to a low-carbon liquid fuel will eliminate appliance cost and reduces the requirement for energy efficiency improvements too, which means cost-effectiveness is maximised.

By contrast, heat pump performance is completely dependent on high building fabric efficiency, which adds significant cost, complexity and disruption to the householder — or a big bill for the taxpayer if the state funds it. Even with slightly higher fuel prices, we think this solution will be attractive to consumers.

Trump weighs using $2 billion in CHIPS Act funding for critical minerals

Codelco cuts 2025 copper forecast after El Teniente mine collapse

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Abcourt readies Sleeping Giant mill to pour first gold since 2014

Nevada army depot to serve as base for first US strategic minerals stockpile

SQM boosts lithium supply plans as prices flick higher

Viridis unveils 200Mt initial reserve for Brazil rare earth project

Tailings could meet much of US critical mineral demand – study

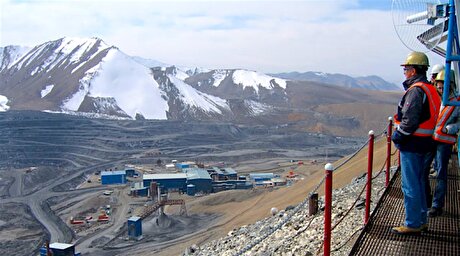

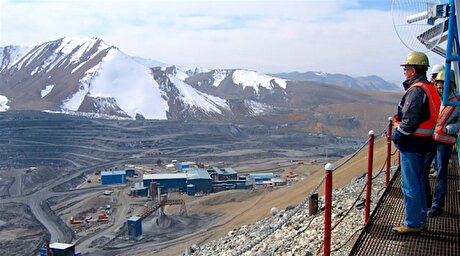

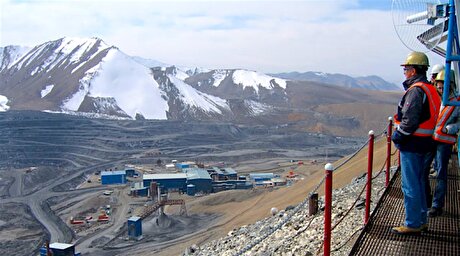

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

KoBold Metals granted lithium exploration rights in Congo

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

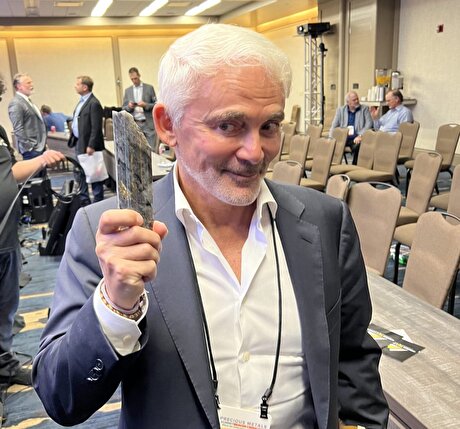

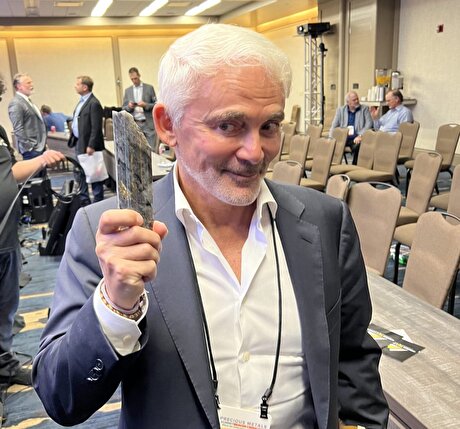

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Silver price touches $39 as market weighs rate cut outlook