Opinion: The spirit of struggle

US president Donald Trump's zero-sum negotiating style with China is not delivering the results he expected. Beijing is taking a much harder line than its previously measured response to the US trade tactics. Washington's threat to impose tariffs on all imports from China has struck a chord of defiance in Beijing, with a senior leader channelling Chairman Mao and the Long March to invoke "the spirit of struggle" in its dispute with the US.

The trade war has so far been cyclical — Trump issues a tariff threat, suspends it to give room to negotiate, then enacts it after failing to extract concessions. His plan to impose tariffs on an extra $300bn/yr of Chinese goods prompted Beijing's unexpected move this week to devalue the yuan. The confrontation is escalating far beyond trade issues, engulfing global financial and commodity markets.

The war of words overwhelmed oil market sentiment this week, with a growing consensus that the intractable trade talks will cause significant damage to the global economy and oil demand growth well into 2020, and possibly much longer.

China's move has raised the prospect of a wider currency war. Trump's response is to label Beijing a "currency manipulator" and to demand that the Federal Reserve slash interest rates further. Yuan weakness and possible competitive currency devaluations by China's neighbours could hit Asia-Pacific crude buying, which accounts for a third of global oil demand and all recent growth.

But energy sector implications do not stop there. Beijing has so far exempted US crude exports from its retaliatory duties, but it is running out of products to target should Trump proceed with the next round of tariffs. The viability of US oil sanctions on Iran and Venezuela is at stake, as Beijing may be tempted to rethink its compliance options to pile pressure on Washington.

Beijing has angrily dismissed the latest US warning that Chinese firms halt business with Caracas. Venezuelan oil shipments serve to pay back $60bn of loans from China, with $16bn outstanding as of July. Iranian shipments to China have fallen from a pre-May average of 460,000 b/d but have not fallen to zero, as US officials had hoped. Washington's success in choking off Tehran's oil export revenue depends on China's compliance, which the US has taken for granted until now.

Claim duck

Washington says it holds leverage over China because of the strong US economy. But Trump's rants against the Fed and his promise of handouts to farmers affected by Beijing's retaliation belie that claim. His focus on boosting US farm product exports — shelving earlier demands that Beijing buy more crude and LNG — reflects his preoccupation with re-election prospects in agricultural states.

White House officials, perhaps influenced by Trump's 1987 ghostwritten guide to negotiations, The Art of the Deal, still believe Chinese delegates will show up in Washington for the next rounds of trade talks in September. But Trump is starting to express doubts. "We will see if we will keep the meeting," he said on 9 August. US energy and business groups hope it takes place, urging Washington to stay the threat of new tariffs. US oil producers once saw China as a key growth market and investment source. They are left hoping that its response to Trump does not permanently cut off crude exports to China.

Gold price edges up as market awaits Fed minutes, Powell speech

Glencore trader who led ill-fated battery recycling push to exit

Emirates Global Aluminium unit to exit Guinea after mine seized

Iron ore price dips on China blast furnace cuts, US trade restrictions

Roshel, Swebor partner to produce ballistic-grade steel in Canada

Trump weighs using $2 billion in CHIPS Act funding for critical minerals

US hikes steel, aluminum tariffs on imported wind turbines, cranes, railcars

EverMetal launches US-based critical metals recycling platform

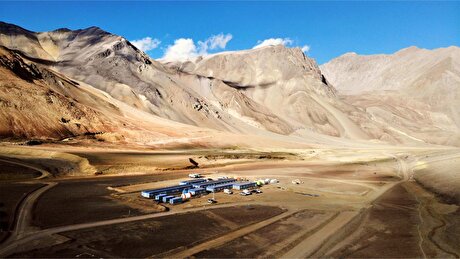

Afghanistan says China seeks its participation in Belt and Road Initiative

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Silver price touches $39 as market weighs rate cut outlook

First Quantum drops plan to sell stakes in Zambia copper mines

Ivanhoe advances Kamoa dewatering plan, plans forecasts

Texas factory gives Chinese copper firm an edge in tariff war

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Silver price touches $39 as market weighs rate cut outlook

First Quantum drops plan to sell stakes in Zambia copper mines

Ivanhoe advances Kamoa dewatering plan, plans forecasts