IMO 2020, EVs, and steel — a perfect storm in the needle coke sector?

Yet the new regulations may have a further, more unexpected effect on the steel sector, and the nascent electric vehicle battery industry, Wood Mackenzie reports.

Indeed, low-sulphur crude oil used to produce needle coke for both graphite electrodes for EAF steelmaking and battery anodes could, in theory, be in short supply. And while China is advancing needle coke capacity using coal tar pitch instead of oil, strict quality requirements mean this substitution could be some way off. With two growing industries – steel and electric vehicles – competing for the same raw materials, could we be heading for a further period of tightness for needle coke?

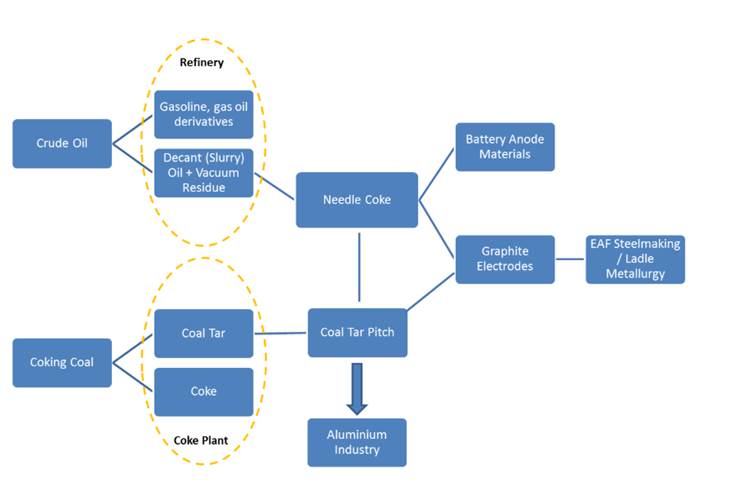

Needle coke 101

Needle coke is a relatively niche product. Its main use by far is in the production of graphite electrodes for the steel industry. These electrodes are used to melt steel scrap, or scrap substitutes, in the case of electric arc furnace (EAF) steelmaking, or to maintain the temperature of molten steel in secondary steelmaking. Needle coke is also employed in the production of synthetic graphite for other uses, including the anode material for lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles.

There are two main types of needle coke. Petroleum needle coke is produced at oil refineries by converting decant or slurry oil, along with high-quality vacuum residue, both by-products of the refining process. Coal-based needle coke (sometimes called ‘pitch needle coke’, or just ‘pitch coke’) is made from coal tar pitch, a by-product of coking metallurgical coal for blast-furnace steelmaking.

Both types of needle coke are distinguished from other varieties of coke by their highly ordered crystalline structure, and its resemblance to vertically aligned needles. They also differ by their quality, which is measured by a low coefficient of thermal expansion and low presence of impurities such as sulphur, nitrogen and ash. It is for these unique characteristics that needle coke typically commands a significant premium over other calcined coke products, such as anode coke – a type primarily used in the aluminium industry.

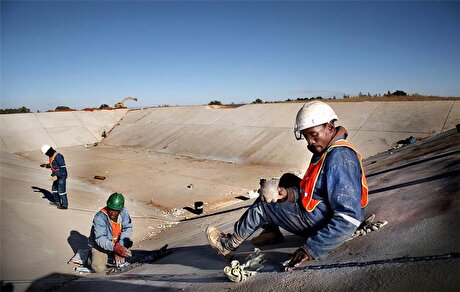

Being a speciality product, and derived from a by-product, needle coke exhibits a concentrated supply structure. There are around 10 major producers globally, with the majority of output being petroleum-based. Most medium-sized refineries, for example, do not have delayed cokers installed, nor the complex coking set-up required to produce speciality products like needle coke.

Only seven producers of any size operate outside China, with Phillips 66 (US and UK) being the largest, followed by Seadrift in the US, and C-Chem, Petrocokes, JX Nippon and Mitsubishi in Japan. Indeed, ex-China capacity has remained broadly flat for the past 10 years given the high capital costs, technical expertise and stringent regulatory processes required to bring on greenfield needle coke projects. In contrast, China is not only a net importer of needle coke but also a large producer, primarily through its coal-based production, with Sinosteel the largest incumbent.

EAF steelmaking – biggest sector to see further growth

By far the biggest use of needle coke is graphite electrodes for steelmaking. These electrodes are an indispensable, industrial consumable, used to conduct electricity during EAF steelmaking, and also to maintain the temperature of liquid steel in steelmaking.

First, a little historical perspective. For much of the past 10 years, interest in needle coke and graphite electrodes has been somewhat muted. This was partly a result of millions of tonnes of Chinese steel finding their way into overseas markets, depressing local prices, lowering operating rates for domestic mills, and ultimately, stymieing demand for consumables like graphite electrodes. Indeed, massive overcapacity and overproduction in the Chinese steel sector saw exports of steel products surge from 43 Mt in 2010, to a peak of 112 Mt in 2015.

Stubborn prices for steel scrap also lowered the competiveness of EAF-based mills relative to their blast furnace-based counterparts. EAF steel output in the world ex-China – battered by excessive exports from China (more than 90% blast furnace based) – declined by around 25 Mt between 2011 and 2015.

All this began to change around 2016 and 2017. Chinese government efforts to rationalise outdated and polluting enterprises saw crude steelmaking capacity alone reduced by 128 Mtpa between 2015 and 2018 – equivalent to the entire capacity of the US. A large chunk of the outdated steel capacity that closed took the form of inefficient induction furnaces (typically producing lower quality steel), with much of this ‘lost’ production shifting to EAF-based mills. Meanwhile, the plants producing needle coke and graphite electrodes also felt the wrath of environmental inspectors, suffering closures as part of the policy to limit air pollution.

While supply-side reforms in China were taking effect, protectionist measures brought in against Chinese steel exports proved a boon to steelmakers in other parts of the world, leading to higher melt rates for EAF steel producers. With a tightening of both needle coke and graphite electrodes supply due to closures, and rising EAF steelmaking demand within China and the rest of the world, prices for needle coke and graphite electrodes both skyrocketed.

While prices have since moderated a little, the trend towards higher EAF production, and therefore graphite electrodes demand, remains on course. This year alone, China plans to commission 15 new EAF units, adding around 6 Mtpa of steel capacity in the year. Meanwhile, seven EAFs with a total annual capacity of 5.5 Mtpa are ramping up. Demand for graphite electrodes and their needle coke feedstock looks set to rise strongly in the coming years.

IMO 2020 – could it tighten supply?

From 1 January 2020, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) will require ships to reduce their emissions to be equivalent to using marine fuels with a maximum sulphur content of 0.5%, reduced from 3.5% currently. The new measures will demand a sizeable response from the maritime industry to comply. Is the shipping industry ready? Probably not. And with limited time to prepare, and some scepticism on enforcement, many may be impacted. Our analysis suggests that the industry will deal with this short-term adaptation through fuel switching (heavy fuel oils, to low-sulphur varieties such as VLSFO and MGO), retro-fitting of vessels to burn low-sulphur or no-sulphur fuels (such as LNG), and by the installation of commercial scrubbers on vessels.

Retro-fitting of vessels will no doubt lead to an increase in costs for ship owners and operators – something likely to manifest itself in higher freight rates, particularly as ships use more marine gas oil. Meanwhile, the option of switching fuels is unlikely to be completely straightforward. We understand refineries have been reluctant to commit the capex for the major upgrades needed to increase production of low-sulphur marine fuel oils. As such, we would expect a tighter market for low-sulphur fuels as ship operators strive to comply.

How does all this affect needle coke? Certainly tighter supply and higher prices seem likely. The reality is that under the new IMO regulations, prices for the low-sulphur crude oil types required to produce needle coke are expected to rise as more of these are diverted towards marine fuels. Needle coke producers would need to contend with either increased competition for feedstock or invest in equipment to allow use of higher sulphur oils. Either way, IMO 2020 is likely to bring higher costs for the main consumer of needle coke – the steel industry.

Electric vehicles – a growing source of demand for needle coke

Graphite is the key material used in the manufacture of anodes (negative electrodes) for lithium-ion batteries. While cathode materials such as lithium cobalt and nickel have received most of the press, graphite is the largest input material by volume into lithium-ion batteries. For example, the Tesla Model S contains up to 85 kg of graphite.

Two types of graphite are used in anode production: synthetic (derived from needle coke) and natural graphite. Despite increasing interest in new projects to mine natural graphite, and its lower cost, battery manufacturers have traditionally preferred synthetic graphite due to its higher purity and consistency. In practice, most use a blend of synthetic with natural to balance performance with cost.

While EV sales are still low, we expect the ongoing electrification of transportation to significantly lift demand for synthetic graphite and needle coke in the coming years. Our EV outlook sees electric passenger cars (with a plug) accounting for 6% of sales by 2025. While a relatively small penetration rate for EVs, even 6% of sales would increase needle coke demand by 250 kt from current levels.

Is a storm brewing?

With demand from steelmaking and lithium-ion batteries expected to see strong growth in the medium term – and question marks over the stability of supply due to the new IMO 2020 restrictions – fundamentals in the needle coke market have the potential to tighten into next year. Moreover, in spite of the higher prices observed in recent years, no greenfield or large-scale brownfield needle coke projects are currently planned. Perhaps testament to the high capital intensity and technical challenges involved.

Yet in China, where supply has come under the microscope of the state authorities in the not too distant past, a new raft of needle coke projects are under development. On one side, high prices for needle coke and the desire to vertically integrate have spurred a number of steel companies and graphite electrode producers to get into the needle coke game. Additionally, a number of mid-sized refineries in Shandong province have been conducting R&D into needle coke production.

We remain somewhat sceptical on this new wave of needle coke supply. Many projects are likely to be delayed, if not cancelled. The few petroleum-based projects, in particular, could suffer from the lack of technical expertise required. Furthermore, sourcing of suitable feed material may prove challenging given tightness in low-sulphur crudes.

While the majority of new Chinese needle coke supply to come to market in the coming years will be coal-based, challenges exist here too. Firstly, environmental controls over metallurgical coke production will continue to limit the supply of coal tar pitch to this new batch of needle coke producers – particularly during the winter heating season when industrial activity is cut for the sake of air quality.

Additionally, there are question marks over the quality of needle coke that might be produced. While all facilities claim to be producing ‘needle coke’, our research suggests that many Chinese plants are producing a lower quality product than the rest of the world. This is the key impediment to China being able to produce large volumes of ultra-high power (UHP) graphite electrodes for steel mills, and explains the country’s continued import dependence on needle coke. Given battery manufacturers also have a preference for petroleum needle coke because of quality reasons, the new capacity additions in China may fall short of demand. A perfect storm for needle coke may well be brewing.

Hindustan Zinc to invest $438 million to build reprocessing plant

Gold price edges up as market awaits Fed minutes, Powell speech

Glencore trader who led ill-fated battery recycling push to exit

UBS lifts 2026 gold forecasts on US macro risks

Roshel, Swebor partner to produce ballistic-grade steel in Canada

Iron ore price dips on China blast furnace cuts, US trade restrictions

Emirates Global Aluminium unit to exit Guinea after mine seized

South Africa mining lobby gives draft law feedback with concerns

EverMetal launches US-based critical metals recycling platform

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Gold price gains 1% as Powell gives dovish signal

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Gold boom drives rising costs for Aussie producers

Vulcan Elements enters US rare earth magnet manufacturing race

Trump raises stakes over Resolution Copper project with BHP, Rio Tinto CEOs at White House

US seeks to stockpile cobalt for first time in decades

Trump weighs using $2 billion in CHIPS Act funding for critical minerals

Nevada army depot to serve as base for first US strategic minerals stockpile

Emirates Global Aluminium unit to exit Guinea after mine seized

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Gold price gains 1% as Powell gives dovish signal

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Gold boom drives rising costs for Aussie producers

Vulcan Elements enters US rare earth magnet manufacturing race

US seeks to stockpile cobalt for first time in decades

Trump weighs using $2 billion in CHIPS Act funding for critical minerals

Nevada army depot to serve as base for first US strategic minerals stockpile

Tailings could meet much of US critical mineral demand – study