From turbines to thermostats: copper miners eye high-tech demand

That bodes well for the likes of Chilean producer Codelco, Rio Tinto Plc and other major copper miners, who are investing billions of dollars to bring new supplies of the metal online during the next 20 years.

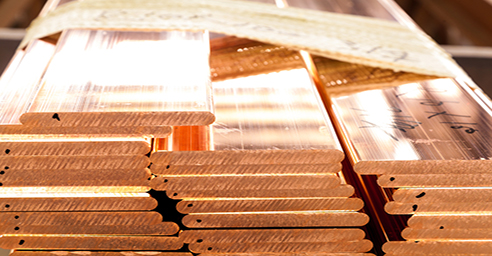

Copper is used to make motors, batteries, wiring and other goods as it is the best electrical-conducting metal, after silver. Aluminum, which is lighter and cheaper than copper, shares some of these traits, but is more corrosive and brittle than its red rival and only about 60 percent as conductive.

"Copper is going to be central to the green revolution," Charlie Durant, a CRU analyst, said at the World Copper Conference this week in Santiago.

So-called smart-home systems – such as Alphabet Inc's Nest thermostat and Amazon.com Inc's Alexa personal assistant – will consume about 1.5 million tonnes of copper by 2030, up from 38,000 tonnes today, according to data from consultancy BSRIA.

"We'll need more copper to meet that demand," Anette Meyer Holley, a BSRIA consultant, said at the conference.

Most smart homes, for instance, use 1,000 meters (0.62 miles) of wiring to connect those devices, containing about 20 kilograms (44 pounds) of copper in total, BSRIA estimates.

Electric vehicles, which use twice as much copper as internal combustion engines, are seen as a major growth area as well, not just for the sheer number of cars expected to be produced, but also battery chemistry.

Attempts to replace copper in a lithium-ion battery's anode with aluminum have failed so far, because lithium reacts with aluminum and corrodes.

"There's lots of skepticism around the use of aluminum in solar and wind, providing a boost for copper" — Benjamin Freas, analyst at Navigant Research

"It's an unfortunate side effect that means copper is essential," Na Jiao, an analyst at consultancy IDTechEx, said at the conference. "Copper is regarded as the best candidate for lithium-ion battery anodes connectors."

Solar panels and wind turbines are also seen as key areas of copper demand growth, with more than 55 percent of copper consumption to come from energy transmission and distribution through 2040, according to the International Energy Administration.

"We know that the future of a modern, efficient digital world is copper," Don Lindsay, chief executive of Canadian miner Teck Resources Ltd, said at the conference.

Aluminum can be used in turbine wiring, but it can shrink inside wiring, potentially causing fires, reducing its appeal.

"There's lots of skepticism around the use of aluminum in solar and wind, providing a boost for copper," said Benjamin Freas, an analyst at Navigant Research, said at the conference.

Copper's appeal pressures miners to produce more, with mines under construction in Panama, Indonesia and even the United States.

"There's likely to be a shortage of copper in the near future due to the electrification trend," John Black, chief executive of junior copper miner Regulus Resources Inc, said at the conference.

In China, which consumes half the world's copper, electronics manufacturers vastly prefer the metal to aluminum due largely to corrosion concerns, said Krisztina Kalman-Schueler of DMM Advisory Group.

"There is not enough motivation to change copper to aluminum across China," Kalman-Schueler said.

Paradoxically, the copper industry sees a boon in the wireless trend, which has sparked concerns about information security and health hazards from radio waves, especially in homes.

"Wireless is king, but concerns over the security and health of wireless will make wiring still very much appealing," Martin Bergemann of Siemens AG said at the conference.

Trump weighs using $2 billion in CHIPS Act funding for critical minerals

Codelco cuts 2025 copper forecast after El Teniente mine collapse

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Abcourt readies Sleeping Giant mill to pour first gold since 2014

Nevada army depot to serve as base for first US strategic minerals stockpile

SQM boosts lithium supply plans as prices flick higher

Viridis unveils 200Mt initial reserve for Brazil rare earth project

Tailings could meet much of US critical mineral demand – study

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

KoBold Metals granted lithium exploration rights in Congo

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Silver price touches $39 as market weighs rate cut outlook