Revitalizing its copper mines may not be sufficient to keep Chile at the fore

Demand for copper is widely expected to take off by the mid-2020s amid a boom in electric vehicle production, but Chile is saddled with mines facing crippling declines in ore grades and a system that allows the bulk of its exploration concessions to sit idle.

Of 300 exploration concessions, just 22 are active. And of the total, big global miners own 89 percent, where juniors own just 4.5 percent, just one-eighth of the global average

"Chile is a fantastic country to work in. The question then comes, if it has all this potential, why are we not seeing growth in exploration?" said Anthony Amberg, of Los Andes Copper, a Canada-based junior with prospects in Chile.

The answer to that question could prove critical as Chilean projects increasingly compete for capital with up and coming greenfield prospects in Congo, Mongolia and even neighboring Peru.

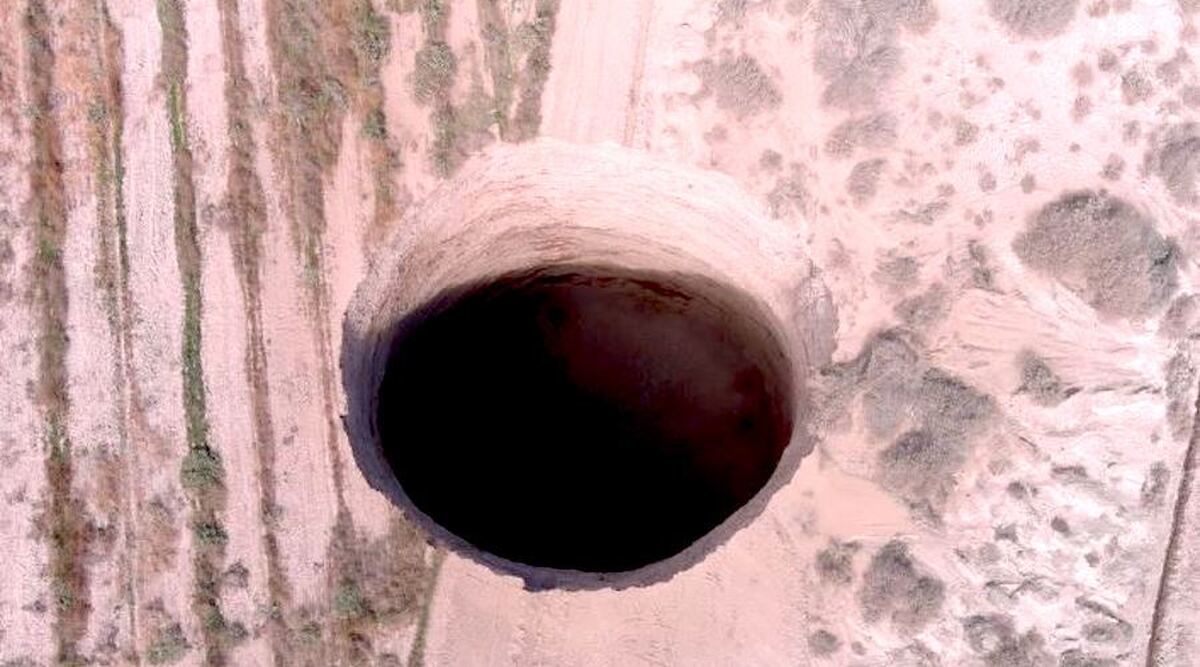

Many of the projects approved and underway in Chile, including a 10-year, $40 billion overhaul drive by the world's top copper producer, Codelco, focus on reinvigorating massive, but sometimes decades or even century-old mines.

The problem has become so severe that Chile's central bank last week cited the issue of declining ore grades as a key reason for slower than anticipated growth in what is normally one of the region's healthiest economies.

"The new structural projects being undertaken by the majors in Chile are mostly about maintaining production, not increasing it," said Chile Deputy Mining Minister Pablo Terrazas. "With a supply deficit on the horizon, we need new projects, new deposits, new discoveries."

At a presentation at the World Copper Conference in Santiago this week, Terrazas said investment in exploration had grown by 19 percent in 2018.

But the numbers are deceptive: Of 300 exploration concessions, just 22 are active. And of the total, big global miners own 89 percent, where juniors own just 4.5 percent, just one-eighth of the global average.

That means many concessions have sat idle for decades or more.

Chile's Mining Ministry this week proposed several solutions, from fostering better financing options for exploration within Chile to hosting roundtable-style conversations with major and junior miners to inspire more turnover in exploration concessions.

Critics say, however, the reforms may not be enough, calling instead for legal changes that would push those with inactive exploration claims to either use them, or lose them

Critics say, however, the reforms may not be enough, calling instead for legal changes that would push those with inactive exploration claims to either use them, or lose them.

Amberg, of Los Andes Mining, said Terraza's plans did not represent a radical change from the status quo.

"It's going to be a very difficult thing to do, politically its very difficult, and it will have to be over multiple governments to implement any change"

"It's going to be a very difficult thing to do, politically its very difficult, and it will have to be over multiple governments to implement any change," Amberg said.

Diego Hernandez, an industry veteran who heads mining trade body Sonami in Chile, agreed that any law change would be unlikely. But he said that existing and planned projects, including Codelco's overhauls and Teck Resources Ltd's Quebrada Blanca 2 expansion, could potentially increase Chile's production by as much as a quarter.

If smaller exploration prospects in Chile continue to fizzle, though, the spike in demand driven by electric vehicles will eventually require supply from new projects, whether from Chile or elsewhere, says Jaime Sepulveda, a copper analyst with CRU.

"In any case, there will be a gap between what we're projecting for demand and what Chile's existing projects can offer," he said.

Trump weighs using $2 billion in CHIPS Act funding for critical minerals

Codelco cuts 2025 copper forecast after El Teniente mine collapse

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Abcourt readies Sleeping Giant mill to pour first gold since 2014

Nevada army depot to serve as base for first US strategic minerals stockpile

SQM boosts lithium supply plans as prices flick higher

Viridis unveils 200Mt initial reserve for Brazil rare earth project

Tailings could meet much of US critical mineral demand – study

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

KoBold Metals granted lithium exploration rights in Congo

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Silver price touches $39 as market weighs rate cut outlook