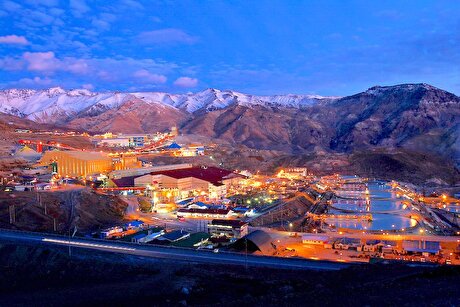

Mongolia lawmakers seek to rewrite Oyu Tolgoi deal

The Gobi desert copper deposit promises to become one of Rio Tinto’s most lucrative properties, but it has been subject to repeated challenges from politicians who argue the spoils of the country’s mining boom are not being evenly shared.

It has also been at the centre of an anti-corruption investigation that has seen the arrest of two former prime ministers and a former finance minister. Nationalist politicians have repeatedly called for the deal to be adjusted in Mongolia’s favour

The original 2009 Oyu Tolgoi Investment Agreement granted 34 percent of the project to the Mongolian government and 66 percent to Canada’s Ivanhoe Mines, now known as Turquoise Hill Resources and majority-owned by Rio Tinto.

Nationalist politicians have repeatedly called for the deal to be adjusted in Mongolia’s favour.

Terbishdagva Dendev, head of a parliamentary working group set up last year to review the implementation of the Oyu Tolgoi agreements, told reporters this week the group had concluded the original 2009 deal should be revised.

A 2015 deal known as the Dubai Agreement, which kickstarted the underground extension of the project after a two-year delay, should also be scrapped entirely, he said.

“Of course there will be international and local pressure, though if we do have rule of law … the agreements should be amended for good,” he said in a separate television interview.

Rio Tinto did not immediately comment on the issue when contacted by Reuters.

A lawyer involved in Mongolian mining deals speaking on condition of anonymity said opponents of the original agreement argue the Dubai Agreement made changes to the 2009 deal and should therefore have been subject to full parliamentary approval. Instead it was just approved by the prime minister.

The 200-page review has been submitted to Mongolia’s National Security Council as well as a parliamentary standing committee on economic matters. It is unclear when or if its recommendations will be implemented.

“It will be very hard to terminate the underground mine plan, since it must be done by mutual agreement,” said Otgochuluu Chuluuntseren, advisor at Mongolia’s Economic Policy and Competitive Research Center and a former government official.

“Also foreign investors who were participating in the project finance might intervene in the process to protect their interests,” he told Reuters, adding that it could also damage investor sentiment for years.

The flagship Oyu Tolgoi project helped spur a mining boom that drove economic growth up to double digits from 2011-2013, but a rapid collapse in foreign investment and falling commodity prices saw Mongolia plunge into an economic crisis in 2016.

Mongolia was also embroiled in a row with Rio Tinto over tax and project budget issues that saw Oyu Tolgoi’s expansion put on hold. A series of other disputes with foreign miners also weakened investor sentiment.

SAIL Bhilai Steel relies on Danieli proprietary technology to expand plate mill portfolio to higher steel grades

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

Fortuna rises on improved resource estimate for Senegal gold project

US slaps tariffs on 1-kg, 100-oz gold bars: Financial Times

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

Fresnillo lifts gold forecast on strong first-half surge

Why did copper escape US tariffs when aluminum did not?

Codelco seeks restart at Chilean copper mine after collapse

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

Hudbay snags $600M investment for Arizona copper project

Discovery Silver hits new high on first quarterly results as producer

Trump says gold imports won’t be tariffed in reprieve for market

AI data centers to worsen copper shortage – BNEF

Uzbek gold miner said to eye $20 billion value in dual listing

Peabody–Anglo $3.8B coal deal on the brink after mine fire

De Beers strikes first kimberlite field in 30 years

Minera Alamos buys Equinox’s Nevada assets for $115M

OceanaGold hits new high on strong Q2 results

What’s next for the USGS critical mineral list

Hudbay snags $600M investment for Arizona copper project

Discovery Silver hits new high on first quarterly results as producer

Trump says gold imports won’t be tariffed in reprieve for market

AI data centers to worsen copper shortage – BNEF

Peabody–Anglo $3.8B coal deal on the brink after mine fire

De Beers strikes first kimberlite field in 30 years

Minera Alamos buys Equinox’s Nevada assets for $115M

OceanaGold hits new high on strong Q2 results

South Africa looks to join international diamond marketing push