Nafta's replacement faces challenges in 2019

Industry executives say they are happy that US President Donald Trump did not follow through on a stated wish to ditch the agreement entirely. But remaining import tariffs on steel and aluminum and the diminishment of legal protections for US investors amid concerns about the future of Mexico's energy reforms have tempered the celebration for some.

US energy firms back the new agreement overall, as it preserves free trade in energy commodities, API senior advisor Aaron Padilla says. But this support is "not because across the board it is better than Nafta — in fact on some key provisions it is not as good. But our comparison is based on no Nafta at all," he says.

Some of the battles fought over Nafta are likely to be replayed when its replacement — the US-Mexico-Canada free trade agreement (USMCA) — is presented for ratification before the countries' respective legislatures in 2019. The deal is due to be signed by 30 November, most likely on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Buenos Aires that will bring together Trump, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau and outgoing Mexican president Enrique Pena Nieto.

Tariffs on imports of steel and aluminium from Canada and Mexico to the US, and retaliatory measures imposed by Ottawa and Mexico City on US agricultural and other exports, are potentially weighing on the ratification process. The USMCA text does not address the issue. But Mexico expects that the three presidents "will have a solution by the time of the signing or at least a very clear track to all parties that a solution is coming", Mexico's ambassador in Washington, Geronimo Gutierrez, says.

Canadian steel industry and labour union representatives have urged the Canadian Parliament not to ratify the agreement unless it addresses the tariffs. US negotiators are pushing Canada and Mexico to accept quotas instead of tariffs, in line with agreements that the US has negotiated with Australia, Argentina, Brazil and South Korea earlier this year. Ottawa has resisted the proposal.

Path of least resistance

The ratification path appears easiest in Mexico, where president-elect Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador's Morena coalition has a majority in both chambers of the legislature. Lopez Obrador's representatives took part in trade negotiations and endorsed the final deal. "The president-elect understands it is important. It will be approved by the Mexican Senate," Gutierrez says.

But the terms Lopez Obrador has extracted for his agreement include the dropping of the dedicated energy chapter in the USMCA, according to his negotiator, Jesus Seade. The final text states that all subsoil oil reserves are the property of the Mexican state, "including the continental shelf and the exclusive economic zone located outside the territorial sea and adjacent thereto". US energy firms had hoped the agreement's energy chapter would enshrine the results of Pena Nieto's historic reform that opened Mexico's energy sector to foreign participation.

Another source of disappointment for the energy sector is the dilution of the so-called investor-state dispute settlement provisions that would allow US companies to have recourse outside of the Mexican legal system. Paradoxically, it was US negotiators who insisted on fully removing the clause from the new agreement. Mexico agreed to preserve that dispute settlement mechanism for US companies. But it will have to compete with the clause asserting Mexico's sovereignty over its natural resources.

Trump weighs using $2 billion in CHIPS Act funding for critical minerals

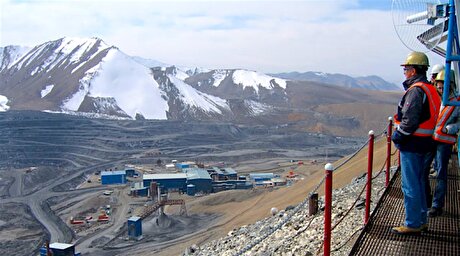

Codelco cuts 2025 copper forecast after El Teniente mine collapse

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Abcourt readies Sleeping Giant mill to pour first gold since 2014

Nevada army depot to serve as base for first US strategic minerals stockpile

SQM boosts lithium supply plans as prices flick higher

Viridis unveils 200Mt initial reserve for Brazil rare earth project

Tailings could meet much of US critical mineral demand – study

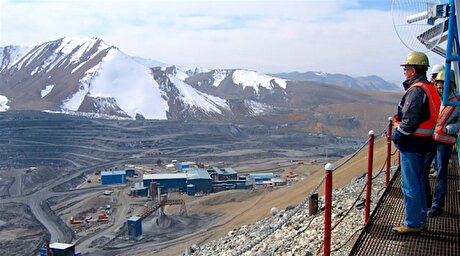

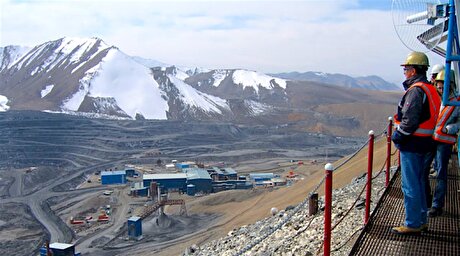

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

KoBold Metals granted lithium exploration rights in Congo

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Silver price touches $39 as market weighs rate cut outlook