World Bank Sees Uptrend in Iran’s GDP Growth to 2019

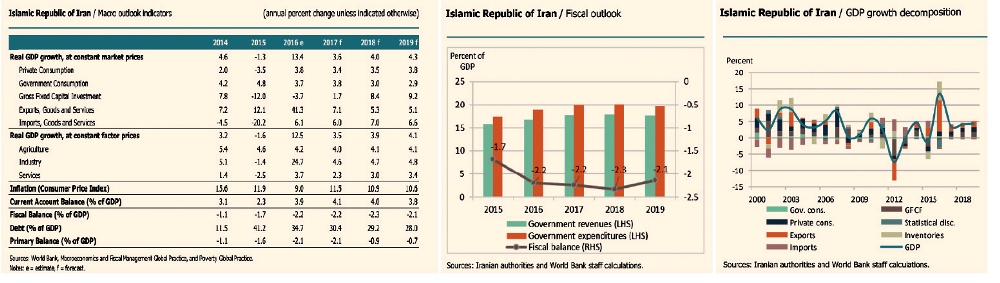

The report estimates a 3.6% GDP growth at constant market prices and 3.5% at constant factor prices for the Iranian economy in 2017. The estimates for 2018 and 2019 are at 4% and 4.3% at constant market prices and 3.9% and 4.1% at constant factor prices respectively.

The World Bank report was released on its website a few days after the International Monetary Fund projected that Iran’s real GDP will expand by 3.5% and 3.8% in 2017 and 2018 respectively. In 2022, the IMF estimates the economic growth will stand at 4.1%.

In the medium term, the Iranian economy is expected to undergo a significant moderation in growth, as spare capacity in the oil sector is utilized.

Iran’s economy took off after the removal of international sanctions over the country’s nuclear energy program in early 2016.

According to World Bank and IMF, Iran experienced an unprecedented 12.5% GDP growth in 2016. The feat was made possible mainly thanks to increased oil output after restrictions on crude sales were lifted as a result of sanctions removal.

However, as crude production is reaching the pre-sanctions level, there is not much room left to see growth in this sector.

As for other economic sectors in 2017, 2018 and 2019, the World Bank expects the agriculture sector to grow at a rate of 4%, 4.1% and 4.1%; the industrial sector at 4.6%, 4.7% and 4.8%; and the services sector at 2.3%, 3% and 3.4% respectively (at constant factor prices).

The World Bank puts growth in the agriculture, industrial and services sectors in 2016 at 4.2%, 24.7% and 3.7% respectively in 2016 (estimated at constant factor prices).

Inflation to Remain Below 12%

With some indications of inflationary pressures due to the closing output gap as well as exogenous commodity price shocks, headline CPI inflation is expected to remain high but below 12% in the next three years especially, considering the high unemployment rate and absence of demand pull factors.

The World Bank is expecting Iran’s inflation rate to reach 11.5%, 10.9% and 10.6% in 2017, 2018 and 2019 respectively.

The IMF forecasts that Iran’s inflation rate will stand at 10.5% and 10.1% in 2017 and 2018 respectively. In 2022, the fund expects the inflation to go below 10% and stand at 8.7% in 2022.

Inflation in Iran reduced to a single digit for the first time after about a quarter century in June 2016. It then followed a downtrend until it bottomed out at 8.6% in the middle of fall. It then rose above 10% in the 12 months ending June 21 this year, before starting to go down since August.

According to the latest report by the Central Bank of Iran, the average Producer Price Index in the 12 months ending Sept. 22, which marks the end of the sixth Iranian month, increased by 8.2% compared with last year’s corresponding period.

Both the IMF and World Bank have put Iran inflation rate in 2016 at 9%.

WB on Economic Developments

In 2016, the economy registered a strong oil-based rebound, with an annual headline growth rate of 13.4%, compared to a contraction of 1.3% in 2015.

The largest contribution to growth was from the industrial sector (at about 25%), as oil and gas production increased by a staggering 62%, mainly as a result of sanctions relief.

Recovery in non-oil GDP, however, was limited at 3.3%, although this represents the highest growth rate in the last five years.

Recent data suggest that growth in crude oil production in the first quarter of 2017 declined to 17% year-on-year.

On the demand side, all components except investment registered improvements over the previous year.

Investment continued to contract in 2016, albeit at a much lower rate of 3.7% (compared to 12% a year earlier). The reduction in investment was primarily driven by the continued contraction in the construction sector since 2012 following a boom in speculative demand for housing.

Despite the growth in non-oil sector, unemployment increased to 12.6% in spring 2017 up from 12.4% six months earlier, which suggests a very limited employment generation capacity in the sectors spearheading growth.

The CBI, together with the Money and Credit Council, has implemented measures to increase investment and non-oil growth. The average interbank interest rate was reduced by 6% to 18.6% in 2016, although the declining trend in 2015 has ended.

The fiscal deficit further widened to 2.2% of GDP in 2016, but the debt to GDP ratio fell to around 35% due to a higher GDP.

The current account surplus increased by more than 80% to reach around 4% of GDP, up from 2.3% in 2015, primarily as a result of increase in oil exports.

However, non-oil merchandise exports declined by 9% in 2016 and recent data for the first four months of the new fiscal year indicate a negative growth in non-oil exports (-10% year-on-year).

The universal cash transfer program appears to have more than compensated for the likely increase in energy expenditures of less well-off households, thus contributing to positive consumption growth of the bottom 40% of the population, with overall consumption growth between 2009 and 2013 being negative.

Poverty increased in 2014 to 10.5% though and this may be associated with a declining social assistance in real terms.

WB on Risks and Challenges

The main risk to the economy is the political uncertainty around the continued implementation of the nuclear agreement, in the wake of new non-nuclear sanctions introduced by the US.

This increases risk perceptions of the country and deters further improvement in foreign investment in the oil and non-oil sectors.

At the same time, delays in the banking sector’s reintegration with global banking, combined with the challenge of fully implementing banking reforms, create further risks for the medium term.

Although CBI has succeeded in reining in shadow banking operations considerably, the issue of high deposit rates, banks’ frozen assets and non-performing loans are yet to be adequately addressed and are major inter-related challenges facing the economy in the foreseeable future.

On the fiscal side, the Ministry of Finance’s attempts in determining the real levels of government debt and securitization of arrears highlights the need for a more comprehensive debt management framework complemented by prudent fiscal policy.

The future prospects of the economy will also depend on the implementation of a wider range of structural reforms, including improving the business environment, productivity, labor market flexibility and further diversification of exports.

Such reforms would also facilitate investment (both domestic and foreign) to achieve a more resilient medium-term growth performance.

Trump weighs using $2 billion in CHIPS Act funding for critical minerals

Codelco cuts 2025 copper forecast after El Teniente mine collapse

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Abcourt readies Sleeping Giant mill to pour first gold since 2014

Nevada army depot to serve as base for first US strategic minerals stockpile

SQM boosts lithium supply plans as prices flick higher

Viridis unveils 200Mt initial reserve for Brazil rare earth project

Tailings could meet much of US critical mineral demand – study

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

KoBold Metals granted lithium exploration rights in Congo

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Silver price touches $39 as market weighs rate cut outlook