Great Opportunity in Recycling Investment

“The recycling industry has a share of less than 0.1% in Iran’s economy,” the secretary-general of Iran Recycling Federation said.

Tohid Sadrnejad also told Financial Tribune that this industry currently makes up 12% and 6% of China’s and Germany’s GDPs respectively.

Iran Recycling Federation was established in 2008 for organizing and developing the Iranian recycling industry. The federation currently has 250 members.

Sadrnejad stressed that recycling, compared to production, takes much less energy and resources.

But that’s not all. Recycling converts the linear economy, which transforms resources into products and then toxic waste, into a circular economy whereby environmental and technical resources are processed and transformed.

It can tremendously help the economy by preventing massive costs inflicted on health, environment and the wasteful use of mines and forest resources.

However, these benefits have been overlooked in the Iranian economy and the need for setting policies supporting the development of recycling industries in the country is felt more than ever.

Dismal Data

The official noted that, according to UN statistics, 23 million tons of garbage are produced in Iran annually and per capita production of solid waste stands at 292 kilograms.

“This is while the rate of material recycling in Iran is about 1-2% while energy recycling is at 3.8-25%,” he said.

Solid waste, commonly known as trash, garbage, refuse or rubbish, consists of everyday data-x-items that are discarded by the public.

Research indicates that food constitutes 75% of Iran’s municipal solid waste.

Sadrnejad said each Iranian produces an average of 800 grams of garbage daily.

Burning garbage, aside from not being economical, releases large amounts of carbon dioxide into the air even if it is done in the most advanced and cleanest furnaces.

Iran is among the top 10 producers of greenhouse gases in the world.

“Over 80% of the country’s wastes are either buried or burned,” he said.

According to Sadrnejad, in view of the current state of the Iranian economy, investors look for opportunities that do not require a great deal of capital.

“Recycling has higher potential of generating value added compared to other economic activities. The industry is an ideal platform for investors,” he said.

Steel Industry Iran’s Most Active Recycling Field

The most active field in Iran’s recycling industry relates to steel recycling from scrap iron, which hardly accounts for one-third of domestic steel production in the country.

For years, Iran’s steel industry has struggled with a shortage of scrap iron.

According to experts, Iranian steel mills’ annual demand for the raw material stands at about 3 million tons, while local scrap producers can only supply half this figure. The country’s ports also lack the infrastructure to import large volumes of scrap iron.

Experts believe that higher scrap iron consumption can help boost the steel industry’s competitive edge by enhancing efficiency. However, Iran’s unbridled direct-reduced iron production and the material’s high availability discourage producers from increasing scrap usage.

“In Iran, cheap energy and abundance of iron ore are the main causes of steelmakers shying away from scrap usage,” says steel industry expert, Taqi Mortazavian.

“This is while most Iranian iron ore is made up of low-grade hematite deposits, the use of which entails a costly beneficiation process. The less pure the mined ore, the higher the volume and m

ore energy is required to turn it to steel.”

According to Mohammad Holakouie, managing director of Tuka Trading Company, scrap metal currently comprises less than 15% of Iranian mills’ annual feedstock.

“Using scrap iron is definitely more efficient, but the market supply is low in the face of rising demand and the government has not taken any measures to address the issue,” he said.

“Boosting scrap supply, from other than government patronage, requires an active construction sector, which is currently deep in recession.”

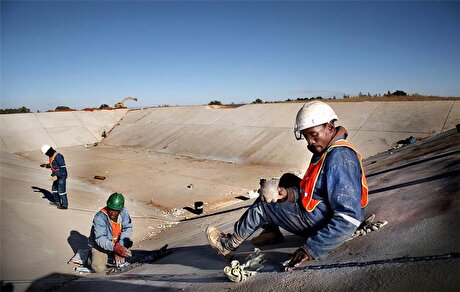

According to Shahram Saber-Tehrani, the head of Khorasan Steel Complex’s Research Department, scrap metal collection and sorting are usually handled manually in unlicensed scrap yards across Iran.

“This outdated method keeps the country’s scrap metal supply below the required industrial level,” he said.

Furthermore, recyclers forgo the crucial process of separating clean from dirty scraps. Hence, steelmakers are compelled to feed their mills with low-quality, environmentally unfriendly scraps while struggling with an unbalanced supply and demand chain in the process.

This is while, according to Holakouie, Iranian industries, especially the auto sector, have high scrap metal production capacity which, if harnessed while complying with global industrial standards, can enhance the steel industry’s output by cutting production costs and increasing product quality.

“Currently, more than 4 million dilapidated cars in Iran, with 350,000-400,000 more being added annually, in addition to 30,000 trucks, buses, minibuses and tractors, need to be scrapped,” he said.

“Cars alone can potentially provide the industry with about 10 million tons of scrap metal.”

Iran’s largest scrap car recycling plant was inaugurated in Zanjan Province in February.

Fuka San’at plant was established with an investment of $6.51 million and an annual production capacity of 180,000 tons of scrap iron.

The German Scholz Holding GmbH holds an 80% stake in the plant and the rest has been financed by an Iranian partner.

Founded in 1872 and based in Essigen, Germany, Scholz Holding collects, sorts, processes, sells and recovers steel scrap and nonferrous metal. The company produces and supplies aluminum and high-grade steel.

Hindustan Zinc to invest $438 million to build reprocessing plant

Gold price edges up as market awaits Fed minutes, Powell speech

Glencore trader who led ill-fated battery recycling push to exit

UBS lifts 2026 gold forecasts on US macro risks

Roshel, Swebor partner to produce ballistic-grade steel in Canada

Iron ore price dips on China blast furnace cuts, US trade restrictions

EverMetal launches US-based critical metals recycling platform

South Africa mining lobby gives draft law feedback with concerns

US hikes steel, aluminum tariffs on imported wind turbines, cranes, railcars

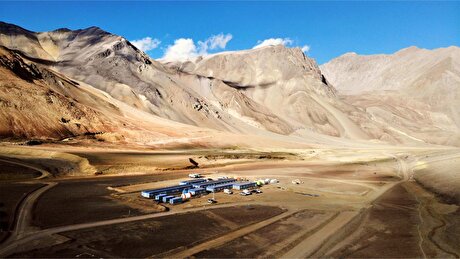

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Gold price gains 1% as Powell gives dovish signal

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Gold boom drives rising costs for Aussie producers

Vulcan Elements enters US rare earth magnet manufacturing race

Trump raises stakes over Resolution Copper project with BHP, Rio Tinto CEOs at White House

US seeks to stockpile cobalt for first time in decades

Trump weighs using $2 billion in CHIPS Act funding for critical minerals

Nevada army depot to serve as base for first US strategic minerals stockpile

Emirates Global Aluminium unit to exit Guinea after mine seized

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Gold price gains 1% as Powell gives dovish signal

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Gold boom drives rising costs for Aussie producers

Vulcan Elements enters US rare earth magnet manufacturing race

US seeks to stockpile cobalt for first time in decades

Trump weighs using $2 billion in CHIPS Act funding for critical minerals

Nevada army depot to serve as base for first US strategic minerals stockpile

Tailings could meet much of US critical mineral demand – study