Bolivia’s lithium deals with China, Russia in limbo

According to me-metals cited from mining.com, The controversy led the Bolivian Chamber of Deputies to suspend parliamentary discussions on the deals in February, pending “a thorough information-sharing process with civil society completed.”

The contracts, worth roughly $2 billion, include a $970 million deal signed last September with Russia’s Uranium One Group (UOG) and a $1 billion agreement with Chinese firms CBC and Citic Guoan Group. Both aim to build lithium processing plants capable of producing tens of thousands of tonnes per year.

President Luis Arce has accused lawmakers of deliberately obstructing these and otcbcher key investments as part of a broader political strategy against his administration.

He warned that if the deals are not approved this year, Bolivia could face a decade-long delay in lithium production. If the country waits too long — until 2035 or 2040 — lithium “will be history,” replaced by other clean energy sources like green hydrogen, he told Russian state media Sputnik earlier this week.

Omar Alarcón, president of state-owned company Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos (YLB) echoed those concerns. He has said failure to approve the contracts could delay industrial-scale production by up to 15 years.

Even if they move forward this year, Bolivia would not begin large-scale lithium production until 2031, energy expert Sergio Hinojosa said in a social media post.

Questionable terms, dubious benefits

Civil society groups, environmental organizations and leaders from the Andean region of Potosí — home to the Uyuni salt flat, one of the world’s largest lithium reserves — have voiced strong concerns. They argue that the deals lack transparency and could lead to severe environmental damage and economic losses.

A key point of contention is the stark cost disparity between the two contracts. The Russian project’s cost per tonne of lithium carbonate production is reportedly 2.4 times higher than the Chinese equivalent, with no clear justification for the difference.

Critics also question the feasibility of the UOG deal, which gives the company just 18 months to build a plant before the contract expires — an unusually short timeline that could leave Bolivia saddled with unfinished infrastructure.

These concerns have fuelled speculation about the deals’ transparency and economic viability, with protesters interrupting a government conference on the contracts.

Under Bolivian law, foreign investors must conduct free, prior and informed consultations with local communities and carry out comprehensive environmental impact assessments before industrial projects can move forward. The agreements must then be approved by the country’s legislature.

With public consultations a full-tilt, government representatives have said at these meetings that Potosi alone would generate estimated royalties of $800 to $900 million over 30 years, equivalent to $30 to $35 million annually.

Delayed lithium dreams

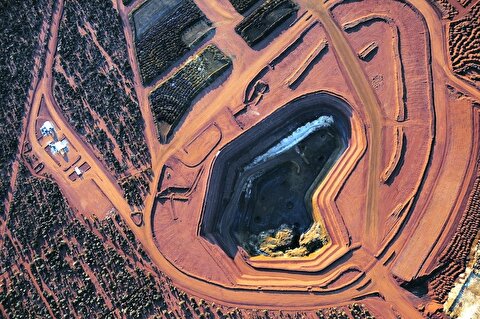

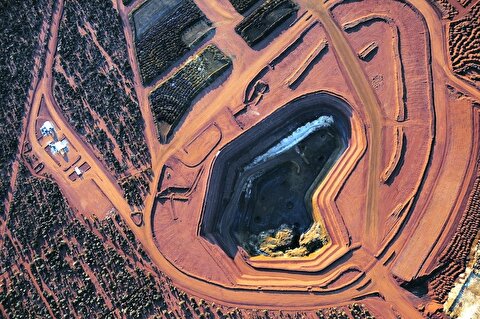

Despite Bolivia’s massive lithium reserves — estimated at 23 million tonnes — the country has struggled for decades to develop a viable lithium industry. Political instability, a state-controlled resource extraction model and high magnesium levels in its lithium deposits have made large-scale production challenging. Unlike neighbouring Chile and Argentina, Bolivia’s lithium remains largely untapped, contributing little to the global supply.

YLB opened Bolivia’s first industrial-scale lithium plant in late 2023, but it operated at only 17% capacity last year and is expected to reach just 23% in 2025.

Meanwhile, government officials, including Vice Minister of Energy Resources Exploitation Raúl Mayta, insist the contracts “are not written in stone” and that they will continue to hold technical meetings with various sectors to address concerns.

The Bolivian government maintains that these partnerships will will fast-track lithium industry development, promising the country will retain 51% of profits.

source: mining.com

Eldorado to kick off $1B Skouries mine production in early 2026

Newmont nets $100M payment related Akyem mine sale

First Quantum scores $1B streaming deal with Royal Gold

Caterpillar sees US tariff hit of up to $1.5 billion this year

Copper price collapses by 20% as US excludes refined metal from tariffs

Gold price rebounds nearly 2% on US payrolls data

St Augustine PFS confirms ‘world-class’ potential of Kingking project with $4.2B value

B2Gold gets Mali nod to start underground mining at Fekola

Copper price posts second weekly drop after Trump’s tariff surprise

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

SAIL Bhilai Steel relies on Danieli proprietary technology to expand plate mill portfolio to higher steel grades

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

Australia weighs price floor for critical minerals, boosting rare earth miners

Australia pledges $87M to rescue Trafigura’s Nyrstar smelters in critical minerals push

Fresnillo lifts gold forecast on strong first-half surge

Why did copper escape US tariffs when aluminum did not?

Fortuna rises on improved resource estimate for Senegal gold project

Caterpillar sees US tariff hit of up to $1.5 billion this year

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

SAIL Bhilai Steel relies on Danieli proprietary technology to expand plate mill portfolio to higher steel grades

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

Australia weighs price floor for critical minerals, boosting rare earth miners

Australia pledges $87M to rescue Trafigura’s Nyrstar smelters in critical minerals push

Fresnillo lifts gold forecast on strong first-half surge

Why did copper escape US tariffs when aluminum did not?

Fortuna rises on improved resource estimate for Senegal gold project