Coal exports choked by green-minded towns on US west coast

On Tuesday, the city of Richmond, California, is expected to approve a ban on coal at a terminal that accounts for almost a quarter of exports from the US West Coast. The prohibition will shut miners out of one of the few places in the region willing to handle the fuel and limit their access to one place in the world where coal demand is still growing.

That’s exactly what Richmond city officials want. “This is something we can do that will almost certainly result in less coal shipped from the U.S. to Asia, and maybe less coal burned in Asia,” Richmond Mayor Tom Butt said in an interview.

Richmond is only the latest West Coast city to fight back against coal passing through the region — an effort to both combat climate change and get rid of the dust coating their towns. Several efforts to build U.S. West Coast coal terminals have failed in recent years amid resistance from environmental groups and local leaders. Washington denied a permit in 2017 for a facility that would’ve shipped as much as 44 million tons a year overseas. The year before that, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers rejected another project in the state.

Oregon also quashed export terminal plans in 2014. And just a few miles away from Richmond, the city of Oakland has banned handling coal, though that decision faces legal challenges.

Several efforts to build U.S. West Coast coal terminals have failed in recent years amid resistance from environmental groups and local leaders

The Richmond city council is set to vote Tuesday night on its ordinance, which would give businesses three years to phase out coal. The legislation targets a port operated by Levin-Richmond Terminal Corp., which last year loaded almost 1 million metric tons of the fuel bound for Japan and South Korea. The ordinance would also include petroleum coke, a byproduct of oil refining and another major product handled by the terminal.

‘Absolute ban’

Gary Levin, the terminal owner’s chief executive officer, didn’t respond to requests for comment. But he said in a July meeting before city officials that the ordinance would impose “an absolute ban on the handling of coal” and would probably put the terminal out of business.

The primary goal of Eduardo Martinez, the Richmond city council member who proposed the ban, is to get rid of the coal dust covering parts of Richmond, a city of about 110,000 on the east side of the San Francisco Bay. But it would be a win for the world, he said.

“It’s obvious to anyone with any capacity to put two and two together that the coal dust is having an impact on health,” Martinez said in an interview. “This is a public health issue — not only for us, but for the world.” Both Butt and Martinez said the ordinance is expected to pass on Tuesday.

The measure amounts to cities making decisions that affect the entire country, said Ashley Burke, a spokeswoman for the National Mining Association. They may face legal challenges, she said.

“Local governments, working with activist environmental groups, cannot be allowed to obstruct and steer interstate and foreign commerce decisions on behalf of the country,” Burke said in an email.

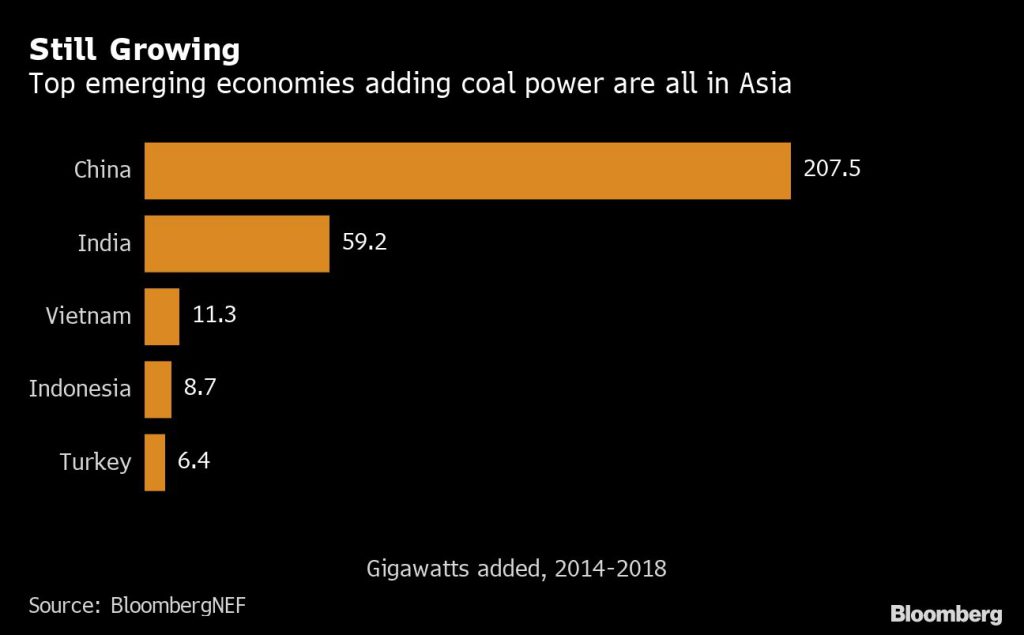

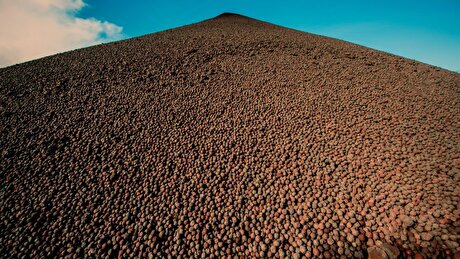

The lack of West Coast export capacity is particularly painful for miners in the Powder River Basin of Montana and Wyoming, America’s biggest coal play, who are trying to get a better price for their fuel overseas. While other parts of the world including the U.S. and Europe are moving away from the fossil fuel, emerging markets continue to build new coal power plants — especially those in Asia.

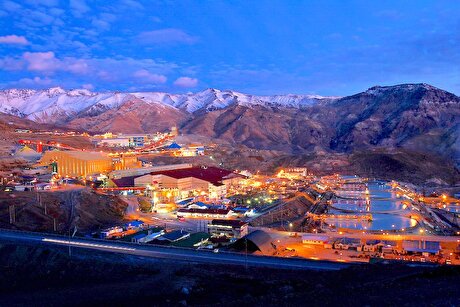

The coal sent from Richmond comes from Utah mines owned by Wolverine Fuels LLC, the state’s biggest producer. The company shipped about 3 million tons to Japan last year through Richmond and nearby Stockton, California. Wolverine’s general counsel didn’t respond to telephone requests for comment.

Richmond, Stockton, Los Angeles and Long Beach in California are now the only major U.S. West Coast ports that handle coal, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. Together, they sent about 4 million tons overseas last year. Another 6 million tons moved through the Seattle area, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, mostly by train to Vancouver, Canada, where it’s loaded onto ships.

No light

Even so, West Coast shipments account for a small portion of U.S coal exports, which totaled 105 million tons last year. Almost 38% of that went to Europe and another 35% to Asia, with India and Japan being the biggest recipients.

Asia’s demand will probably end up being met by miners outside of the U.S., most notably Indonesia and Australia, said Andrew Cosgrove, a mining analyst with Bloomberg Intelligence.

“There’s no light at the end of the tunnel for West Coast coal exports,” Cosgrove said. “What can producers do? There’s really not much they can do.”

Codelco seeks restart at Chilean copper mine after collapse

Hudbay snags $600M investment for Arizona copper project

Uzbek gold miner said to eye $20 billion value in dual listing

BHP, Vale offer $1.4 billion settlement in UK lawsuit over Brazil dam disaster, FT reports

Peabody–Anglo $3.8B coal deal on the brink after mine fire

A global market based on gold bars shudders on tariff threat

SSR Mining soars on Q2 earnings beat

Minera Alamos buys Equinox’s Nevada assets for $115M

Century Aluminum to invest $50M in Mt. Holly smelter restart in South Carolina

Samarco gets court approval to exit bankruptcy proceedings

US eyes minerals cooperation in province home to Reko Diq

Allegiant Gold soars on 50% financing upsize

Explaining the iron ore grade shift

Metal markets hold steady as Trump-Putin meeting begins

Trump to offer Russia access to minerals for peace in Ukraine

Gemfields sells Fabergé luxury brand for $50 million

Gold price stays flat following July inflation data

Eco Oro seeks annulment of tribunal damage ruling

Zimbabwe labs overwhelmed as gold rally spurs exploration, miner says

Samarco gets court approval to exit bankruptcy proceedings

US eyes minerals cooperation in province home to Reko Diq

Allegiant Gold soars on 50% financing upsize

Explaining the iron ore grade shift

Metal markets hold steady as Trump-Putin meeting begins

Trump to offer Russia access to minerals for peace in Ukraine

Gemfields sells Fabergé luxury brand for $50 million

Gold price stays flat following July inflation data

Eco Oro seeks annulment of tribunal damage ruling