Even a lifelong copper bull isn’t sure the next move will be up

Yet even the five-decade metals veteran and copper bull acknowledges the miserable mood seeping through the industry’s annual gathering in London this week. For now, any talk of constraints on new supply or higher consumption as the world’s cities expand is drowned out by worries about sagging demand fueled by the U.S.-China trade war.

It’s a dramatic shift from a year ago, when just about everyone in the industry was bullish on the metal used in pipes and wires.

“The fundamentals for the market are very positive in the short-, mid- and long-term, but the mood is not that great,” Targhetta said in an interview. “We keep hoping and expecting that when the uncertainties clear up, it will jump in a vivid way.”

Global demand will drop this year for copper, aluminum, zinc and lead, according to CRU’s estimates

At about $5,900 a ton, London Metal Exchange copper is near the bottom of a tight range it’s held since the trade war broke out in mid-2018. Mounting evidence of a consequential collapse in manufacturing output has helped to keep a lid on prices even as supply issues stack up.

The gloomy sentiment at this year’s LME Week isn’t limited to copper. Commodities consultancy CRU Group on Tuesday offered a downbeat assessment of the prospects for industrial metals in the coming year. Global demand will drop this year for copper, aluminum, zinc and lead, according to CRU’s estimates.

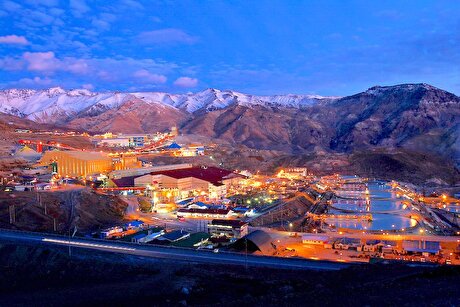

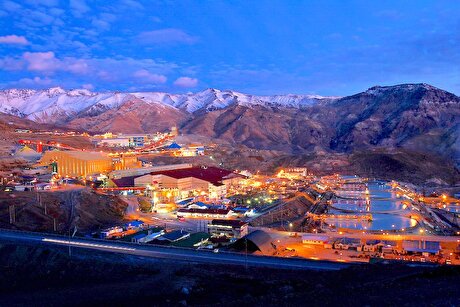

There are even doubts that nickel — the star performer this year — may struggle to hold its gains in the face of deteriorating demand. Nickel’s rally has been fueled by an expedited ban on raw ore exports from Indonesia, and a sharp drawdown in inventories on the LME. Nickel’s supply shock has been too big for traders to ignore, but they’ve been happier to discount simmering issues in top copper producer Chile, where the worst social unrest in decades has led to disruptions at several major ports and mines.

“The mood is not that great”

Javier Targhetta, Freeport-McMoRan

Mine supply in the copper market is already constrained, and Freeport will push for a further reduction in the processing fees it pays smelters to reflect that tightness, Targhetta said.

So-called treatment charges for mined copper concentrates were set at a six-year low of $80.80 per ton of processed ore this year, and it wouldn’t be surprising to see them fall below $70, he said.

Copper ore is becoming harder to find and mine, which means the industry will struggle to meet the world’s needs, Targhetta said.

There’s also plenty of compelling reasons on the demand side to bet on higher prices, he said.

Freeport calculates that the mining industry will need to find an additional 100 million tons of copper over the next two decades to feed rising consumption in renewable energy, electrified transport and urbanization projects, he said.

That’s about five times current annual output, and isn’t far short of the 160 million tons of additional metal that was needed over two decades to feed China’s unprecedented economic expansion, Targhetta said.

First Quantum scores $1B streaming deal with Royal Gold

Newmont nets $100M payment related Akyem mine sale

Caterpillar sees US tariff hit of up to $1.5 billion this year

Gold price rebounds nearly 2% on US payrolls data

Goldman told clients to go long copper a day before price plunge

Australia pledges $87M to rescue Trafigura’s Nyrstar smelters in critical minerals push

Copper price posts second weekly drop after Trump’s tariff surprise

One dead, five missing after collapse at Chile copper mine

Idaho Strategic rises on gold property acquisition from Hecla

Century Aluminum to invest $50M in Mt. Holly smelter restart in South Carolina

Australia to invest $33 million to boost Liontown’s Kathleen lithium operations

Glencore warns of cobalt surplus amid DRC export ban

SSR Mining soars on Q2 earnings beat

A Danieli greenfield project for competitive, quality rebar production

China limits supply of critical minerals to US defense sector: WSJ

Alba Hits 38 Million Safe Working Hours Without LTI

Advanced cold-rolled strip for China’s New Energy Vehicle market

Codelco seeks restart at Chilean copper mine after collapse

US slaps tariffs on 1-kg, 100-oz gold bars: Financial Times

Australia to invest $33 million to boost Liontown’s Kathleen lithium operations

Glencore warns of cobalt surplus amid DRC export ban

SSR Mining soars on Q2 earnings beat

A Danieli greenfield project for competitive, quality rebar production

China limits supply of critical minerals to US defense sector: WSJ

Alba Hits 38 Million Safe Working Hours Without LTI

Advanced cold-rolled strip for China’s New Energy Vehicle market

Codelco seeks restart at Chilean copper mine after collapse

US slaps tariffs on 1-kg, 100-oz gold bars: Financial Times