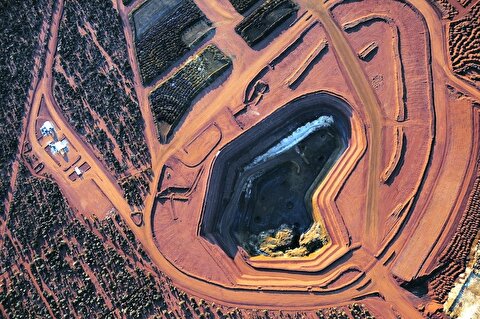

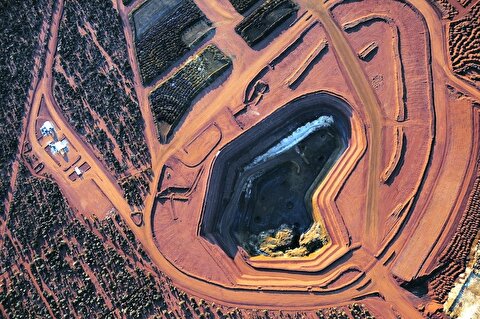

China develops taste for high-grade iron ore as coastal furnaces fire up

Relocating plants to the coast, with stricter environmental requirements, means up to 20% of China's more-than-a-billion-tonne annual ore demand will shift from lower- to higher-grade ores within coming years, according to industry sources and a Reuters analysis of official import and production statistics.

Steel executives say the demand shift in the top ore market will mean declining purchases of low-grade supplies and greater demand for pelletised ore of a higher grade - with potentially major implications for ore exporters in Australia.

"Iron ore producers who can sell pellet-feed into China will be better placed than those who don't have such products," said Ian Roper, general manager at Shanghai Metals Market, a Chinese metals market research company, "with the major Australian (lower-grade) specialist suppliers facing the biggest challenge in the medium to longer term."

Brazil's Vale SA (VALE3.SA), the world's biggest iron ore miner, is also the top producer of pellets and pellet feed. LKAB in Sweden and Switzerland-based Ferrexpo (FXPO.L) are the second- and third-largest pellet producers.

Vale declined to comment for this article, but directed Reuters to its Aug. 1 quarterly earnings call, where it stated pellet production would be 45 million tonnes for 2019, down from 55 million tonnes in 2018 due to outages at some of its Brazilian operations. LKAB and Ferrexpo declined to comment.

BIGGER, CLEANER, PICKIER

Over a four-year campaign against pollution, as well as excess capacity in heavy industry, China has shut 700 small steel mills with 140 million tonnes of steel capacity deemed sub-standard, plus 150 million tonnes of inefficient capacity at larger firms.

Remaining mills will need to further cut emissions, and those located in the smog-prone eastern rust belt must move to designated steel parks along the coast, where fragile eco-systems mean environmental regulations are strict.

More than 50 Chinese steel companies pledged in 2018 to shut old capacity and build new furnaces with a combined yearly capacity of 60.29 million tonnes, according to a Reuters analysis of official industry data. Nearly 25 million tonnes of this new capacity is scheduled to come on line in 2020.

Another 33 firms will build 47.03 million tonnes of new capacity within the next three years.

These new plants will each house bigger, more efficient furnaces with annual capacity of more than 1 million tonnes, compared to 550,000-650,000 tonnes previously.

They will also boast lower emissions but require higher quality ore and more pellets to minimize pollution and optimize output, industry experts said.

"It's much more expensive to fix big furnaces than the smaller ones," said a purchasing manager at a mid-sized mill in Hebei, China's steel hub. "So mills tend to feed them with better raw materials, and adding more pellets will improve air permeability in the furnaces."

The manager declined to be identified as he is not authorized to talk to media.

PELLET PROS & CONS

Iron ore pellets, typically with 64% iron content or above, can be shoveled directly into blast furnaces without going through a dirtier process known sintering, where low-grade ore is mixed with other products to create a blast furnace fuel.

"Using pellets in steelmaking consumes only one third of the energy that using sinter ore does," said Li Xishan, assistant general manager at Yangzhou Pacific Special Materials Co, the biggest pellet producer in China, with annual capacity of 6 million tonnes.

Emissions of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide will be cut by 47-95% if mills cut out sintering and switch to pellets, Li said.

Erik Hedborg, senior iron ore analyst at CRU in London, expects Chinese pellet demand to grow more than 40% by 2023 to roughly 190 million tonnes, from 140 million tonnes in 2018, and keep rising.

China's current demand for pellets remains well below overseas counterparts, at around 15-16% of all ore compared with 35% in Europe.

"We expect China to follow the rest of the world in terms of pellet rates," Hedborg said.

While using pellets effectively shifts part of the dirty production process offshore, they are more expensive than lower-grade ore.

So far this year, pellet-grade ore for import has averaged $30 per ton above low-grade 58% ore, and about $12 a ton more than benchmark-grade 62% ore, according to data from consultancy Steelhome.

This means any significant increase in pellet purchases may come with a hefty price tag for cash-strapped mills.

HOME-GROWN OR SHIPPED IN?

Due to those enduring cost concerns, much of the initial increase in pellet demand is expected by industry insiders to be filled by domestic producers, who have a combined output production capacity of 253 million tonnes and often undercut international rivals.

But analysts question whether domestic suppliers will be able to keep up with demand, given their own emissions restrictions and limited supplies of pellet feed.

"We expect pellet feeds production in China to fall amid the tightening environmental regulations," said Dr. Ming He, senior manager at Wood Mackenzie in Beijing. "Hence mills will have to buy pellets directly from foreign producers, as the cost of making pellets with imported feeds would be too expensive."

China imported 18.67 million tonnes of pellets last year, or 1.8% of total iron ore imports, with 34% coming from India, 26% from Canada and 14% from Brazil, according to Chinese customs data.

Newmont nets $100M payment related Akyem mine sale

First Quantum scores $1B streaming deal with Royal Gold

Caterpillar sees US tariff hit of up to $1.5 billion this year

Copper price collapses by 20% as US excludes refined metal from tariffs

Gold price rebounds nearly 2% on US payrolls data

St Augustine PFS confirms ‘world-class’ potential of Kingking project with $4.2B value

B2Gold gets Mali nod to start underground mining at Fekola

Copper price posts second weekly drop after Trump’s tariff surprise

Goldman told clients to go long copper a day before price plunge

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

SAIL Bhilai Steel relies on Danieli proprietary technology to expand plate mill portfolio to higher steel grades

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

Australia weighs price floor for critical minerals, boosting rare earth miners

Australia pledges $87M to rescue Trafigura’s Nyrstar smelters in critical minerals push

Fresnillo lifts gold forecast on strong first-half surge

Why did copper escape US tariffs when aluminum did not?

Fortuna rises on improved resource estimate for Senegal gold project

Caterpillar sees US tariff hit of up to $1.5 billion this year

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

SAIL Bhilai Steel relies on Danieli proprietary technology to expand plate mill portfolio to higher steel grades

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

Australia weighs price floor for critical minerals, boosting rare earth miners

Australia pledges $87M to rescue Trafigura’s Nyrstar smelters in critical minerals push

Fresnillo lifts gold forecast on strong first-half surge

Why did copper escape US tariffs when aluminum did not?

Fortuna rises on improved resource estimate for Senegal gold project