China resumes work on three key projects in Iran despite US sanctions

For the first of these projects – Phase 11 of the supergiant South Pars non-associated gas field – last week saw a statement from the chief executive officer of the Pars Oil and Gas Company (POGC) that talks had resumed with Chinese developers to advance the project, the Energy news website wrote on Wednesday.

Originally the subject of an extensive contract signed by France’s Total before it pulled out due to reimposed US sanctions on Iran, talks had been well-advanced with the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) to take up the slack on development. As per the original contract, CNPC had been assigned Total’s 50.1 percent stake in the field when the French firm withdrew, giving it a total of 80.1 percent in the site, with Iran’s own Petropars Company holding the remainder.

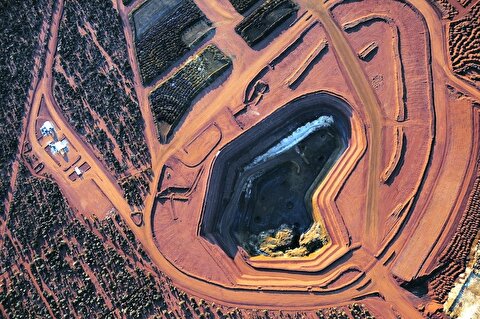

At the same time, Iran was anxious to increase the pace of development of the fields in its oil-rich West Karoun area, including North Azadegan, South Azadegan, North Yaran, South Yaran, and Yadavaran, in order to optimize oil flows ahead of further clampdowns on exports by the US.

China, though, which at that time was engaged in just the opening shots of the trade war with the US was loathe to completely disregard all US sensibilities when it came to Iran but equally saw itself as a longstanding partner of the Islamic Republic, always being cognizant of its need to ensure diversity of energy supply.

At that point, China agreed a trade-off with the US that in exchange for it halting active development of Phase 11 of the South Pars it would be allowed to continue its activities in North Azadegan and would be able to go ahead with its development of Yadavaran – the second of China’s major Iran projects.

China told the US that its continued involvement in North Azadegan could easily be justified to anyone else who might be interested on the basis that it had already spent billions of dollars developing the second phase of the 460-square-kilometer field. Similarly, China said at the time, its ongoing activities on Yadavaran could be justified by the fact that the original contract had been signed in good faith in 2007, way before the US withdrawal from the nuclear deal in May 2018 and thus, legally speaking, it had every right to go ahead.

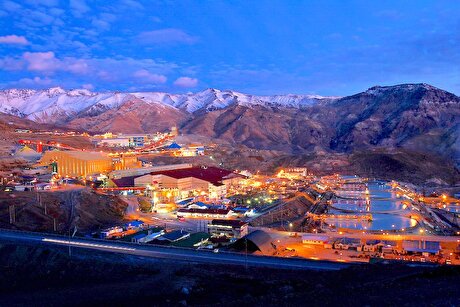

The third of China’s major as yet unfinished projects in Iran was the build-out of the Jask oil export terminal, which lies in the Gulf Of Oman. Even before the new US sanctions, the Kharg export terminal was not ideal for use by tankers as the narrowness of the Strait of Hormuz means that they have to go very slowly through it.

So, according to the plans, a $2 billion or so 1,000-kilometer oil pipeline will connect Guriyeh in the Shoaybiyeh-ye Gharbi Rural District, in Khuzestan Province (southwest Iran), to Jask county, in Hormuzgan Province (south Iran), with any financing required over and above that provided for Iran to be made readily available from China.

Also to be constructed in Jask is an initial 20 storage tanks each capable of storing 500,000 barrels of oil, and related shipping facilities, at a cost of around $200 million. Overall, the intention is for Jask to have the capacity to store up to 30 million barrels and export one million barrels per day of crude oil. There are adjunct plans to build a large petrochemicals and refining complex in Jask as well, with the prime market for produced petchems – including gasoline, gas oil, jet fuel, sulfur, butadiene, ethylene and propylene, and mono-ethylene glycol – again being China.

According to a recent comment by the director of projects at Iran’s National Petrochemical Company, Ali-Mohammad Bossaqzadeh, the project would be built and run by Bakhtar Petrochemicals Holding, although “other foreign companies” may take part. In fact, according to the Iran source, China has also offered to send as many engineers and other professionals required in such a project to Iran for as long as necessary.

In order for it to reactivate its development of SP11, China will get a 17.25 percent discount for nine years on the value of all gas it recovers.

“This is the value of the gas as applied to CNPC’s cost-return formula against the open market valuation, and currently the net present value of the site is $116 billion,” the Iranian source told the Oil Price.

For its part, China has agreed to increase the production from its oil fields in the West Karoun area – including North Azadegan and Yadavaran – by an additional 500,000 bpd by the end of 2020. This dovetails with Iran’s plan to increase the recovery rate from these West Karoun fields that it shares with Iraq from the current 5 percent (compared to Saudi Arabia’s 50 percent).

“For every one percent increase, the recoverable reserves figure would increase by 670 million barrels, or around $34 billion in revenues with oil even at $50 a barrel,” the Iran source said.

China’s ‘nuclear option’

If there is any further pushback from the US on any of these Chinese projects in Iran, then Beijing will invoke in full force the “nuclear option” of selling all or a significant part of its $1.4 trillion holding of US Treasury Bills, with a major chunk of the paper due to be sold in September on this basis.

This massive holding of these bonds – through which the US finances its economy and is an important factor both in the value of the dollar and therefore in the health of US international companies especially – has been used as a bargaining chip before by China, especially when it feels threatened.

Back in 2007, just before the great financial crisis, a number of senior Chinese figures at various state-run think tanks stated that the large-scale selling of this massive Treasury Bill holding would trigger a dollar crash, a huge spike in bond yields, the collapse of the housing market and stock market chaos.

Such a tactic would neatly fit into China’s overall strategy to have the renminbi challenge the US dollar’s status as the key global reserve currency and the prime currency for global energy transactions.

“The long-planned sequencing for this was inclusion in the SDR [Special Drawing Rights] mix, which happened in 2016, increasing use as a trading currency, which followed that, use as the key currency of an international energy trading exchange, which has occurred with the creation of the renminbi-denominated Shanghai International Energy Exchange in last year, and the calls from big oil producers and other major trading nations to use the renminbi, which has been happening over the past few years,” the head of a New York-based commodities hedge fund told the Oil Price.

Only recently, Leonid Mikhelson, the chief executive officer of Russian oil major, Novatek, said that future sales to China denominated in renminbi is under consideration and that US sanctions accelerate the process of Russia trying to switch away from US dollar-centric oil and gas trading and the damage from potential sanctions that go with it.

“This has been discussed for a while with Russia’s largest trading partners such as India and China, and even Arab countries are starting to think about it... If they do create difficulties for our Russian banks then all we have to do is replace dollars,” he said. “The trade war between the US and China will only accelerate the process,” he added.

The trade war with the US, though, may be the very reason why this policy is not being pushed right now by China, Rory Green, Asia economist for TS Lombard told the Oil Price.

“With the renminbi weakening, and set to reach 7.50 to the [US] dollar level if the US imposes 25 percent tariffs on all Chinese exports, it is more difficult for China to persuade the big oil producers like Russia, Iran, Iraq, Venezuela, to make the switch away from the dollar,” he said.

“For China as well, the timing is not quite right, as its use of Eurodollar financing is currently significant, it has a lot of dollar-denominated bonds rolling over shortly, and its balance of payments needs a relatively healthy US demand profile, but China wants to get away from the dollar system and that is the overall direction of travel,” he concluded.

Newmont nets $100M payment related Akyem mine sale

First Quantum scores $1B streaming deal with Royal Gold

Caterpillar sees US tariff hit of up to $1.5 billion this year

Gold price rebounds nearly 2% on US payrolls data

Copper price collapses by 20% as US excludes refined metal from tariffs

St Augustine PFS confirms ‘world-class’ potential of Kingking project with $4.2B value

B2Gold gets Mali nod to start underground mining at Fekola

Goldman told clients to go long copper a day before price plunge

Copper price posts second weekly drop after Trump’s tariff surprise

Codelco seeks restart at Chilean copper mine after collapse

US slaps tariffs on 1-kg, 100-oz gold bars: Financial Times

BHP, Vale offer $1.4 billion settlement in UK lawsuit over Brazil dam disaster, FT reports

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

SAIL Bhilai Steel relies on Danieli proprietary technology to expand plate mill portfolio to higher steel grades

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

Australia weighs price floor for critical minerals, boosting rare earth miners

Australia pledges $87M to rescue Trafigura’s Nyrstar smelters in critical minerals push

Fresnillo lifts gold forecast on strong first-half surge

US slaps tariffs on 1-kg, 100-oz gold bars: Financial Times

BHP, Vale offer $1.4 billion settlement in UK lawsuit over Brazil dam disaster, FT reports

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

SAIL Bhilai Steel relies on Danieli proprietary technology to expand plate mill portfolio to higher steel grades

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

Australia weighs price floor for critical minerals, boosting rare earth miners

Australia pledges $87M to rescue Trafigura’s Nyrstar smelters in critical minerals push

Fresnillo lifts gold forecast on strong first-half surge