Green Steel: How Arkansas Became Home To America's Cleanest And Fastest-Growing Steelmaker

Overlooking the action there’s a control room with a lone operator in front of a dozen LCD monitors displaying graphics representing data from thousands of sensors on nearly every piece of equipment in the 1.76-million-square-foot flat-rolled steel mill. One display uses an optical emission spectrometer to analyze the composition of the molten steel in real time, determining the amount of alloys like copper in the mix. A red display shows that the furnace—no more than 60 feet away—is at 2,951 degrees Fahrenheit.

Man of Steel: CEO David Stickler believes his little Big River mill can outproduce the most efficient plants in places like China.Tim Pannell for Forbes

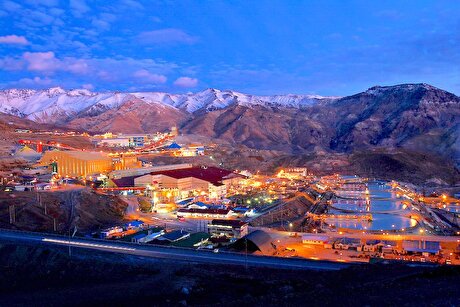

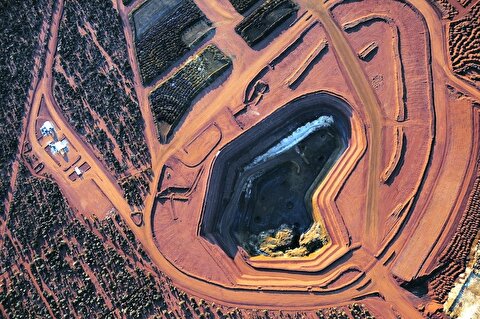

Welcome to Osceola, Arkansas (pop. 6,764), onetime home of legendary blues guitarist Albert King and headquarters to Big River Steel, the future of steel production on the planet. The mini mill, which is producing 4,500 tons of hot-rolled steel each day or about 1.65 million per year, began operating only 31 months ago thanks to almost $1 billion in high-yield-debt financing, a slug of equity from Koch Industries, Arkansas’ teachers’ pension fund, private equity firm TPG Capital and the sheer operating zeal of a little-known investment banker named David Stickler.

“We view ourselves as a technology company that just happens to make steel,” says Stickler, pounding his fist on a table for effect.

Though tiny relative to North Carolina’s Nucor, Big River is hands down the most technologically advanced and fastest-growing steel producer in North America. With only 513 employees its cash flow per employee amounts to a whopping $557,000 compared to integrated producer U.S. Steel’s $61,000. The next most efficient mini mill competitor, Steel Dynamics, operates at $253,000 per employee. It takes just one hour for Big River to produce a 35-ton coil of hot-rolled steel compared to days at an integrated steel producer.

Including bonus pay, the average Big River production worker earned $129,000 last year, 3.5 times the median household income in Arkansas’ Mississippi County. Big River has already secured enough financing to double its capacity to 3.3 million tons by the end of 2020.

Casual Friday: Once named best dressed in Beijing, Stickler’s wife, Rebecca Li, holds no official role at Big River, but her Chinese connections have been critical.Tim Pannell

Back in the control room a monitor flashes, automatically recommending a modification to the operating parameters. “Ultimately, the operators won’t have to do anything. The machines will adjust themselves,” says Stickler, 58, noting that the information from his sensors is being transmitted to a data center where an artificial intelligence system developed by Noodle.ai and Dell runs predictive algorithms. Stickler likens his mill to a self-driving car. “The Google and Apple cars, the more they drive, the more they learn. The more this mill operates, the more it’s learning.”

Stickler’s transformation from banker to steel company CEO wasn’t planned. A Cleveland native and former accountant, he spent 15 years as an investment banker, mostly working on financing big steel, including the $385 million Bain Capital used to launch Indiana’s Steel Dynamics.

In the mid-1990s he met his future wife, Rebecca Li, a vivacious Chinese wellness consultant who was showing a friend Hawaiian real estate. Li helped him make connections in Asia, and in 1998 he raised $650 million to build a mill in Thailand. Stickler also courted Nucor’s CEO, John Correnti, who tapped him in 1999 to finance a restructuring of Birmingham Steel. In 2003, Stickler and Li formed Global Principal Partners, a steel-focused merchant bank.

Over the next decade, the firm raised some $6 billion for numerous projects ranging from modernizing a mill for Tangshan Steel in China to SeverCorr, a Mississippi mill it sold to a Russian steel giant in 2008. Correnti handled plant operations, and Stickler and Li, the dealmakers, traveled the world and maintained homes in New York, Los Angeles, Beijing and Thailand. Around 2013, Correnti and Stickler decided that their next project would be a new U.S-based state-of-the-art electric mini mill.

“There was somewhat of a revolution under way,” says Stickler, noting how U.S. makers were rapidly losing global market share.

After getting incentives and funding from Arkansas and local municipalities, Stickler chose Osceola, a small town about 50 miles north of Memphis, downriver from massive scrap metal yards in cities like Chicago, adjacent to Burlington Northern rail lines and close to major trucking routes I-40 and I-55. Entergy offered it rock-bottom power rates through 2026.

However, 13 months into the construction of the mill, in August 2015, Big River CEO Correnti died in his sleep while in Chicago attending a Navistar board meeting. “My plan was not to be CEO of Big River Steel,” says Stickler. “John passed away on a Tuesday. By Friday of that week, we had completely reorganized.”

One of Correnti’s strategies that Stickler boasts about is Big River’s Wall Street-style bonuses. The majority of mill workers have production bonus targets amounting to 150% of their wages, so a technician earning a base of $18 per hour is expected to take home at least $45 an hour. “We’ve had weeks where people are getting paid a bonus of 180%, 200% or even 210%,” says Stickler.

Another differentiator at Big River is its LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification. “Typically it’s for university and government buildings,” says Stickler. “A lot of people thought we were nuts to try and qualify for it.” Stickler believes it will make the difference whether it is selling to Chrysler, Volkswagen or Walmart. “People won’t pay more for our steel because it’s produced in a LEED-certified facility, but everything else being equal: price, service, quality, etc., we get the order,” says Stickler.

Last year, thanks to a strong backdraft created by Trump’s 25% steel tariffs and fear of shortages, prices hit a ten-year high, allowing Big River to book revenues of $1.4 billion.

“I’m not okay with tariffs,” retorts Stickler. “Trump has given the domestic steel industry an opportunity to get itself on the right path. But we don’t need tariffs to survive and thrive.”

If there is one big question mark surrounding Big River’s future, it may be its ability to thrive under its $1.5 billion debt load. In May, the steel startup got the Arkansas Development Finance Authority to lend its name to $487 million in 30-year junk municipal bonds to finance expansion. According to Moody’s, the bonds will boost the company’s leverage ratio to a risky 6.8 times and drop its interest coverage ratio to one or less.

A ramp-up in global production has created a glut in flat-rolled steel, and prices have fallen by 25% in 2019. But Stickler seems unconcerned. He’s gearing up for another $500 million debt/equity financing that will enable Big River to manufacture the specialized steel that goes into hybrid and electric cars. The dealmaker in him knows that he will likely be able to flip Big River-—at big profit—long before its debts come due.

Last summer in fact, Nucor reportedly offered as much as $3 billion for Big River, but Stickler rejected the deal. Thanks to assistance from his wife, Big River has been hosting tours for dozens of visiting company executives from around the world. “We don’t hide behind patents and IP,” boasts Stickler.

One notable group was a team of executives, including its chairman, from the second-largest steelmaker in the world, China’s state-owned Shanghai Bao Steel, which produces about 45 million tons a year. A beaming Li says, “They told David he was the Steven Jobs of steel.”

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

US slaps tariffs on 1-kg, 100-oz gold bars: Financial Times

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

Codelco seeks restart at Chilean copper mine after collapse

Uzbek gold miner said to eye $20 billion value in dual listing

Hudbay snags $600M investment for Arizona copper project

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

BHP, Vale offer $1.4 billion settlement in UK lawsuit over Brazil dam disaster, FT reports

Australia weighs price floor for critical minerals, boosting rare earth miners

Zimbabwe labs overwhelmed as gold rally spurs exploration, miner says

Cochilco maintains copper price forecast for 2025 and 2026

Adani’s new copper smelter in India applies to become LME-listed brand

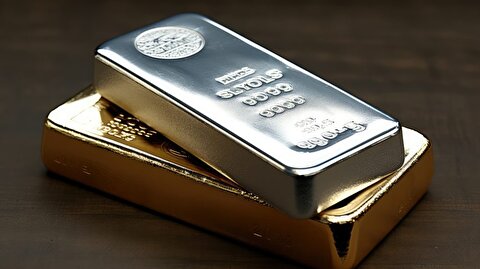

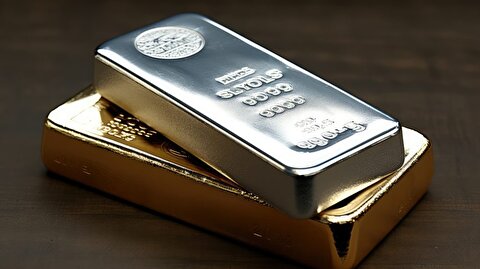

HSBC sees silver benefiting from gold strength, lifts forecast

Mosaic to sell Brazil potash mine in $27M deal amid tariff and demand pressures

Samarco gets court approval to exit bankruptcy proceedings

Hudbay snags $600M investment for Arizona copper project

Discovery Silver hits new high on first quarterly results as producer

Trump says gold imports won’t be tariffed in reprieve for market

AI data centers to worsen copper shortage – BNEF

Cochilco maintains copper price forecast for 2025 and 2026

Adani’s new copper smelter in India applies to become LME-listed brand

HSBC sees silver benefiting from gold strength, lifts forecast

Mosaic to sell Brazil potash mine in $27M deal amid tariff and demand pressures

Samarco gets court approval to exit bankruptcy proceedings

Hudbay snags $600M investment for Arizona copper project

Discovery Silver hits new high on first quarterly results as producer

Trump says gold imports won’t be tariffed in reprieve for market

AI data centers to worsen copper shortage – BNEF