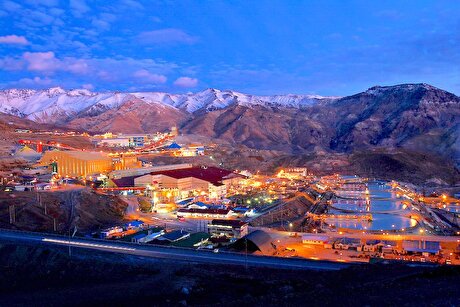

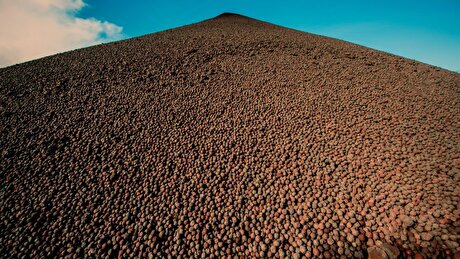

Wall at Vale's Gongo Soco pit begins gradual slide; dam holds

“These pieces settled gently at the bottom of the pit with early assessments indicating that the wall is sliding gradually, verifying evaluations that any further slippage should occur without major consequence,” Vale said.

Local authorities had initially feared that a landslide at Gongo Soco could destabilize the nearby Sul Superior dam, causing damages and polluting the nearby town of Barão de Cocais.

Vale said the Sul Superior dam, located just 1.5 km from the mine, remains intact and that it continues to be monitored 24/7 with systems capable of detecting the slightest movements

Vale, however said the dam, located just 1.5 km from the mine, remains intact and that it continues to be monitored 24/7 via radar, drones and a robotic station capable of detecting the slightest movements.

Sul Superior dam has been at level 3 alert, which is the highest classification, since late March. Almost 700 people living close to it were preventively evacuated in early February after monitoring systems detected abnormal movement in the northern slope of the pit.

Though residents of Barão de Cocais later returned to their homes, they have been living with the possibility of the dam’s rupture and an emergency evacuation.

They have also been living with the recent memory of a dam burst at Vale’s Córrego do Feijão mine, also in the state of Minas Gerais, which killed 242 people and devastated the nearby town of Brumadinho in January.

Under Scrutiny

Brazil has since banned the construction of new upstream dams, which are cheaper but less stable than other types of tailings dams, and ordered the decommissioning of existing ones.

In March, the company was hit by a local court injunction that forced it to freeze operations at 13 of its tailings dams in the South American country. Under pressure from federal and state prosecutors for failing to do enough to prevent the disaster, Vale named company veteran Eduardo Bartolomeo as chief executive to replace Fabio Schvartsman, who stepped down after the incident.

Shortly after, Brazilian prosecutors began probing more than 100 high-risk dams across the country. They say they doubt the legitimacy of the safety audits carried out at the nation’s mines, especially considering that Córrego do Feijão was certified as stable by German consulting group Tüv Süd only days before the deadly accident.

Gongo Soco is one of 87 mining dams in Brazil built like the one that failed in January. All but four have been rated by the government as equally vulnerable, or worse.

The next few hours, experts say, will reveal how the Sul Superior dam reacts to the disintegrating debris coming down from the slope, though Vale insists that any further slippage should not have any major consequence.

Codelco seeks restart at Chilean copper mine after collapse

Hudbay snags $600M investment for Arizona copper project

Uzbek gold miner said to eye $20 billion value in dual listing

BHP, Vale offer $1.4 billion settlement in UK lawsuit over Brazil dam disaster, FT reports

Peabody–Anglo $3.8B coal deal on the brink after mine fire

A global market based on gold bars shudders on tariff threat

SSR Mining soars on Q2 earnings beat

Minera Alamos buys Equinox’s Nevada assets for $115M

Century Aluminum to invest $50M in Mt. Holly smelter restart in South Carolina

Samarco gets court approval to exit bankruptcy proceedings

US eyes minerals cooperation in province home to Reko Diq

Allegiant Gold soars on 50% financing upsize

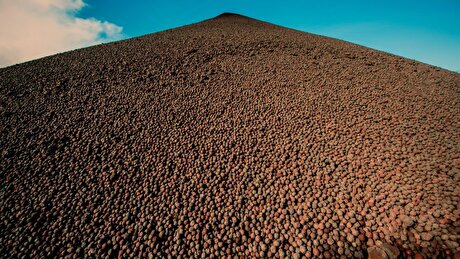

Explaining the iron ore grade shift

Metal markets hold steady as Trump-Putin meeting begins

Trump to offer Russia access to minerals for peace in Ukraine

Gemfields sells Fabergé luxury brand for $50 million

Gold price stays flat following July inflation data

Eco Oro seeks annulment of tribunal damage ruling

Zimbabwe labs overwhelmed as gold rally spurs exploration, miner says

Samarco gets court approval to exit bankruptcy proceedings

US eyes minerals cooperation in province home to Reko Diq

Allegiant Gold soars on 50% financing upsize

Explaining the iron ore grade shift

Metal markets hold steady as Trump-Putin meeting begins

Trump to offer Russia access to minerals for peace in Ukraine

Gemfields sells Fabergé luxury brand for $50 million

Gold price stays flat following July inflation data

Eco Oro seeks annulment of tribunal damage ruling