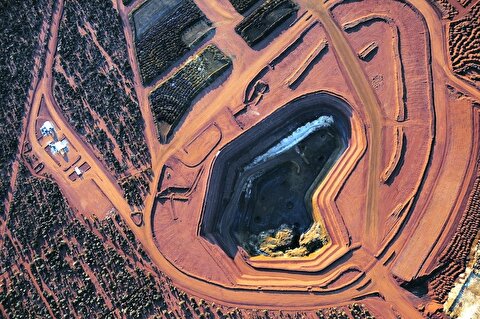

Copper miner's $10B bet comes to life in Panama jungle

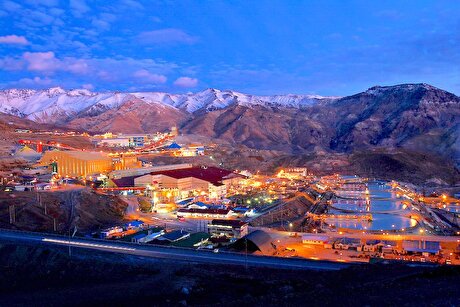

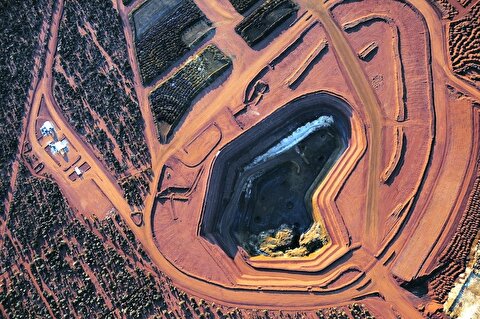

Cobre Panama, a vast mining and processing complex near Panama’s Atlantic coast, processed its first ore on Monday, a half century after the deposit was discovered. At full production in 2021, it will turn Vancouver-based First Quantum into a top copper producer alongside giants like Freeport-McMoRan Inc. and BHP Group.

For Panama, it’s the biggest investment ever outside the canal and makes the Central American country a key supplier to a copper market facing labor unrest and governments grasping for greater takes. The $6.3 billion project will be able to ship its concentrate, thanks to the Panama Canal, to just about any smelter in the world.

“This establishes a new jurisdiction for mining,” Tristan Pascall, the project’s general manager, said in an interview at the facility shortly before the first ore passed through its mills. “There aren’t many projects coming on.”

Past failures

It’s been a long time coming. For 50 years the deposit had remained tantalizingly but steadfastly out of reach.

“Possibly vast beds could rival Panama Canal as economic asset to country,” the Star & Herald, a local English-language newspaper, trumpeted on the front page of its May 1, 1968 edition after a United Nations survey team discovered the deposit.

Past attempts to develop it all met with failure. The terrain undulates like an egg carton — impossible to navigate for colossal mining equipment. When it rains, as it often does, the soil turns into a maddening toothpaste-like clay. A Japanese consortium of seven companies and Teck Resources Ltd. abandoned it. In 2013, First Quantum took it on after a C$5 billion ($3.8 billion) takeover of Canadian rival Inmet Mining Corp., which had spent two decades on the project with little to show for it. Most in the mining industry had written off Cobre Panama.

‘Too-hard box’

“It was a project that all the major mining companies had put in the too-hard box,” says Clive Newall, co-founder and president of First Quantum.

It seems they were wrong.

In the six years since, the Canadian miner has managed to level the daunting terrain, at times filling in trenches 60 meters deep. It built a deep-water port where mining trucks the size of a suburban house can roll in fully assembled off ships. It built a coal-fired power plant and Panama’s third road connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Kjell Anzelius, 85, the only surviving member of the original U.N. survey team, began seeing stories about the mine in the news last year. When he realized that the deposit he’d helped discover was on the cusp of production, he hopped on a plane from his home in Sweden.

Newmont nets $100M payment related Akyem mine sale

First Quantum scores $1B streaming deal with Royal Gold

Caterpillar sees US tariff hit of up to $1.5 billion this year

Gold price rebounds nearly 2% on US payrolls data

Copper price collapses by 20% as US excludes refined metal from tariffs

St Augustine PFS confirms ‘world-class’ potential of Kingking project with $4.2B value

Goldman told clients to go long copper a day before price plunge

B2Gold gets Mali nod to start underground mining at Fekola

Copper price posts second weekly drop after Trump’s tariff surprise

Codelco seeks restart at Chilean copper mine after collapse

US slaps tariffs on 1-kg, 100-oz gold bars: Financial Times

BHP, Vale offer $1.4 billion settlement in UK lawsuit over Brazil dam disaster, FT reports

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

SAIL Bhilai Steel relies on Danieli proprietary technology to expand plate mill portfolio to higher steel grades

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

Australia weighs price floor for critical minerals, boosting rare earth miners

Australia pledges $87M to rescue Trafigura’s Nyrstar smelters in critical minerals push

Fresnillo lifts gold forecast on strong first-half surge

US slaps tariffs on 1-kg, 100-oz gold bars: Financial Times

BHP, Vale offer $1.4 billion settlement in UK lawsuit over Brazil dam disaster, FT reports

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

SAIL Bhilai Steel relies on Danieli proprietary technology to expand plate mill portfolio to higher steel grades

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

Australia weighs price floor for critical minerals, boosting rare earth miners

Australia pledges $87M to rescue Trafigura’s Nyrstar smelters in critical minerals push

Fresnillo lifts gold forecast on strong first-half surge