Miners are budgeting for a recovery in copper

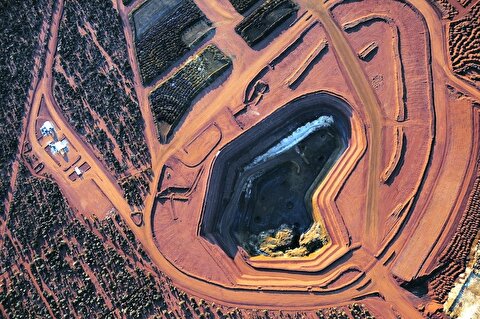

Right now, that suggests that the recent gloomy outlook for copper may not last. More than a third of capital spending by big diversified miners is being dedicated to the metal at the moment, up from levels of 20 percent or less earlier in the decade. That represents a substantial bet that forecast deficits for copper over the next decade will indeed materialize.

Aluminum, zinc, and platinum-group metals are currently running red-hot, too – but iron ore, petroleum and fertilizers seem to be fatally out of fashion.

To get an idea of where mining executives are allocating their capital, we’ve combed through the past five years of reports from the eight major diversified miners that have a real choice of where they spend their money – BHP Group, Rio Tinto Group, Vale SA, Anglo American Plc, Glencore Plc, South32 Ltd., Vedanta Resources Plc and Teck Resources Ltd.

The trend underlying all this is the way capital spending collapsed after the boom in the early part of this decade, and is yet to show strong signs of recovery. Mining executives are still donning the sackcloth-and-ashes of “disciplined capital allocation,” which they took up to atone for the vast sums of wasted cash during the market’s last peak.

Still, the enforced diet doesn’t apply equally to all commodities. Copper is eating up an outsize share of budgets right now, with just shy of $8 billion spent by our group of companies over the 12 months through June.

The turn in aluminum and zinc is even more pronounced. Whereas spending on copper is still well down from five years ago, those two elements are running at more or less the same level in dollar terms, despite the fact that capex as a whole is about a third of what it was in 2013. Platinum-group metals are in a similar situation, suggesting that the recent record high for palladium is more than just a one-off.

Looking at capital spending isn’t a pure measure of miners’ tastes. BHP, the industry’s top spender, has an exaggerated impact on the overall picture. The ebbing of its vast expenditures on petroleum under pressure from shareholders including Elliott Management Corp. accounts for most of the collapse in that category, despite ongoing outlays by Teck and Vedanta.

Its retreat from the potash fertilizer business – along with Vale’s simultaneous move away from crop nutrients – accounts for the majority of the spending decline in that area. And the slowing of iron ore spending from a $21.3 billion annual run-rate to $5.3 billion between December 2013 and June 2018 is almost entirely down to BHP, Vale and Rio Tinto, with a little help from Anglo American.

Capital spending remains a useful corrective at those times when miners are trying to sell you a narrative they don’t really buy themselves. Despite optimistic noises made by several miners about nickel during its run up to more than $15,000 a metric ton in June, no one is really spending money to develop more of it – with the exception of Glencore, whose Koniambo deposit has the virtue of being unusually high-grade, so better able to survive periods of weak pricing.

Similarly, thermal coal is yet to really pick itself up from the spending levels plumbed in 2015 and 2016, despite prices that touched a five-year high this year. A segment that accounts for more than half of revenue and 30 percent of Ebitda at Glencore only managed to get about 10 percent of that company’s expansion capex in 2017. That sounds like a business being run for cash, rather than one with a glowing future.

It’s the job of miners to spin a positive story for the hunks of rock that end up in their portfolio, but it’s a good idea to look at capex before getting too caught up in their prognostications. If mining executives aren’t prepared to spend money on a commodity, why should investors?

Newmont nets $100M payment related Akyem mine sale

First Quantum scores $1B streaming deal with Royal Gold

Caterpillar sees US tariff hit of up to $1.5 billion this year

Gold price rebounds nearly 2% on US payrolls data

Copper price collapses by 20% as US excludes refined metal from tariffs

St Augustine PFS confirms ‘world-class’ potential of Kingking project with $4.2B value

Goldman told clients to go long copper a day before price plunge

B2Gold gets Mali nod to start underground mining at Fekola

Copper price posts second weekly drop after Trump’s tariff surprise

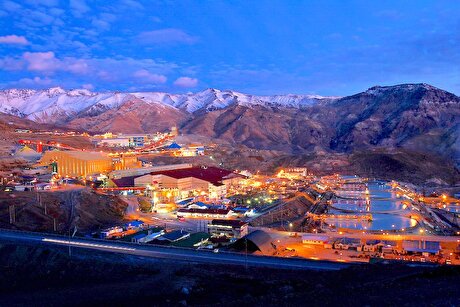

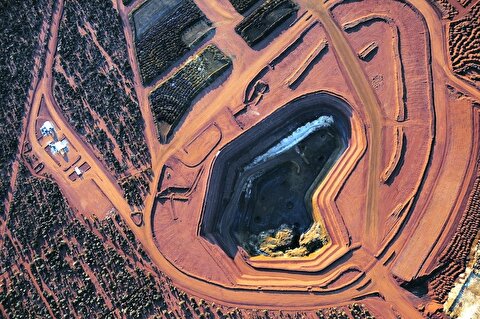

Codelco seeks restart at Chilean copper mine after collapse

US slaps tariffs on 1-kg, 100-oz gold bars: Financial Times

BHP, Vale offer $1.4 billion settlement in UK lawsuit over Brazil dam disaster, FT reports

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

SAIL Bhilai Steel relies on Danieli proprietary technology to expand plate mill portfolio to higher steel grades

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

Australia weighs price floor for critical minerals, boosting rare earth miners

Australia pledges $87M to rescue Trafigura’s Nyrstar smelters in critical minerals push

Fresnillo lifts gold forecast on strong first-half surge

US slaps tariffs on 1-kg, 100-oz gold bars: Financial Times

BHP, Vale offer $1.4 billion settlement in UK lawsuit over Brazil dam disaster, FT reports

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

SAIL Bhilai Steel relies on Danieli proprietary technology to expand plate mill portfolio to higher steel grades

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

Australia weighs price floor for critical minerals, boosting rare earth miners

Australia pledges $87M to rescue Trafigura’s Nyrstar smelters in critical minerals push

Fresnillo lifts gold forecast on strong first-half surge