Global warming 1.5 degrees C goal needs 73-97% cut to coal: IPCC

The report suggests policies and technologies will be needed to enable a transition from coal, and to a lesser extent oil, to cleaner forms of energy, while also allowing for longer dependency on emissions-intensive lifestyles if carbon capture technologies are deployed.

The report shows that oil will be able to maintain its role as the backbone of global energy until 2030 when coal has been largely phased down, but will itself face a rapid drop to 2050, requiring massive increases in the use of nuclear energy, renewables and biomass, as well as natural gas, to meet growing global energy demand.

However, the IPCC considered four model pathways to achieve a net emissions reduction consistent with the 1.5 C target, which included a wide range of scenarios with implications for energy production.

The pathways ranged from a downsized global energy system that enables a rapid decarbonization of energy supply through to a resource and energy intensive scenario where economic growth and globalization lead to widespread adoption of greenhouse gas intensive lifestyles, including high demand for transportation fuels and livestock products, requiring emissions reductions through technological progress and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage.

Based on all four pathways, to stay within the global target, coal use for primary energy would have to fall by 59-78% from 2010 levels by 2030, and by 73-97% by 2050.

Oil and gas showed a less clear picture, ranging from sharp cuts to significant increases in use across the four pathways, depending on the use of technologies to capture CO2 emissions.

Primary energy from oil could range between a drop of 37% and a rise of 86% from 2010 levels by 2030, and fall by 32%-87% by 2050, it said.

Primary energy from gas could range between a drop of 25% and an increase of 37% from 2010 levels by 2030, and between a drop of 74% and an increase of 21% by 2050, the IPCC said.

The IPPC's middle-of-road scenario showed that a rapid phase-out of coal will allow oil's consumption to continue little changed until 2030, beyond which rapid falls would be required. To meet global final energy demand growth of 17% by 2030 and 21% by 2050, increased use of nuclear power, renewable energy and biomass will be required, it said.

Under the middle scenario, global CO2 emissions need to fall by 41% from 2010 levels by 2030 and by 91% by 2050.

Under the same scenario, primary energy from coal falls by 75% from 2010 levels by 2030 and by 73% by 2050, while primary energy from oil falls by 3% from 2010 levels by 2030 and by 81% by 2050.

Primary energy from natural gas increases by 33% from 2010 levels by 2030 and by 21% by 2050, while primary energy from nuclear power rises by 98% from 2010 levels by 2030 and by 501% by 2050.

Renewable energy's share of electricity rises by 48% from 2010 levels by 2030 and by 63% by 2050, while primary energy from biomass increases by 36% from 2010 levels by 2030 and by 121% by 2050.

The IPCC's report helps to set out emissions reduction pathways ahead of UN climate change talks running December 3-14 in Katowice, Poland, where governments are working on ways to deliver the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change.

Keeping global warming within the 1.5 C limit is still possible within the laws of chemistry and physics, but doing so would require unprecedented changes, the IPCC said in a statement Monday.

The panel also said global action to address the problem would bring benefits.

"With clear benefits to people and natural ecosystems, limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees compared with 2 degrees could go hand in hand with ensuring a more sustainable and equitable society," the IPCC said.

Under the Paris Agreement, governments asked the IPCC to produce a special report by the end of 2018 on global warming of 1.5 C and related greenhouse gas emissions pathways.

"One of the key messages that comes out very strongly from this report is that we are already seeing the consequences of 1 degree C of global warming through more extreme weather, rising sea levels and diminishing Arctic sea ice, among other changes," said Panmao Zhai, co-chair of the IPCC's Working Group I, which looks into the physical scientific basis of climate change.

"This report gives policymakers and practitioners the information they need to make decisions that tackle climate change while considering local context and people's needs. The next few years are probably the most important in our history," said Debra Roberts, co-chair of the panel's Working Group II, which studies the mitigation of climate change.

Global warming of about 1 C has already taken place since pre-industrial levels and the 1.5 degrees C level is likely to occur between 2030 and 2052 if it continues at the current rate, the IPCC said.

The Paris Agreement includes voluntary commitments by governments, known as Nationally Determined Contributions, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of fossil fuels, agriculture and land use, in a coordinated effort to reach the global targets. Under the Paris process, governments are set to undertake periodic stocktakes of collective efforts so far, and consider where further work is needed.

Governments see scope to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from many areas of the economy, including replacing the most emissions-intensive coal-fired power plants with renewable energy; shifting from fossil fuels to cleaner energy in the transport sector including road transport, aviation and shipping; energy efficient buildings; low emissions industrial processes; and changes to land use, forestry and agriculture.

The IPCC's report contains more than 6,000 scientific references and includes contributions from thousands of experts and government reviewers worldwide. The panel's findings have to undergo multiple reviews prior to publication to ensure objectivity and transparency, and its reports are approved by governments.

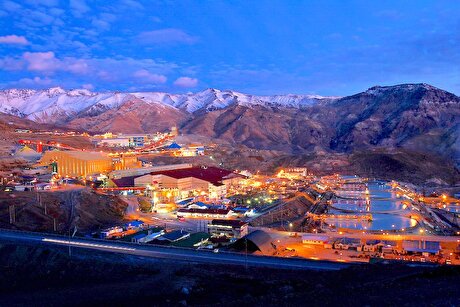

Codelco seeks restart at Chilean copper mine after collapse

Uzbek gold miner said to eye $20 billion value in dual listing

Hudbay snags $600M investment for Arizona copper project

BHP, Vale offer $1.4 billion settlement in UK lawsuit over Brazil dam disaster, FT reports

Peabody–Anglo $3.8B coal deal on the brink after mine fire

A global market based on gold bars shudders on tariff threat

Minera Alamos buys Equinox’s Nevada assets for $115M

SSR Mining soars on Q2 earnings beat

Century Aluminum to invest $50M in Mt. Holly smelter restart in South Carolina

Cleveland-Cliffs inks multiyear steel pacts with US automakers in tariff aftershock

Bolivia election and lithium: What you need to know

Samarco gets court approval to exit bankruptcy proceedings

US eyes minerals cooperation in province home to Reko Diq

Allegiant Gold soars on 50% financing upsize

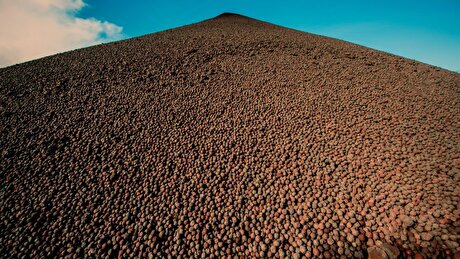

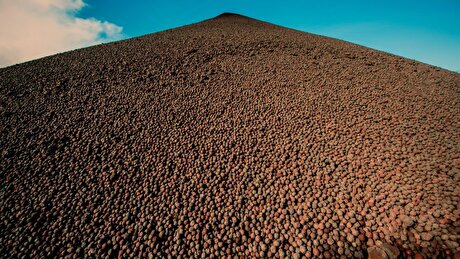

Explaining the iron ore grade shift

Metal markets hold steady as Trump-Putin meeting begins

Trump to offer Russia access to minerals for peace in Ukraine

Gemfields sells Fabergé luxury brand for $50 million

Gold price stays flat following July inflation data

Cleveland-Cliffs inks multiyear steel pacts with US automakers in tariff aftershock

Bolivia election and lithium: What you need to know

Samarco gets court approval to exit bankruptcy proceedings

US eyes minerals cooperation in province home to Reko Diq

Allegiant Gold soars on 50% financing upsize

Explaining the iron ore grade shift

Metal markets hold steady as Trump-Putin meeting begins

Trump to offer Russia access to minerals for peace in Ukraine

Gemfields sells Fabergé luxury brand for $50 million