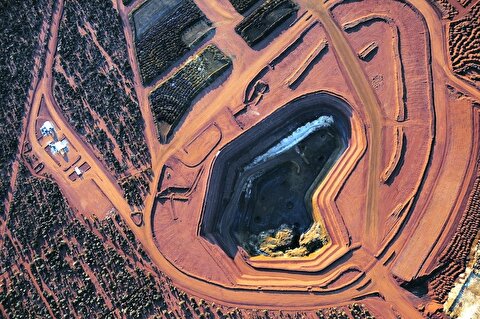

Copper supply crunch earlier than predicted

According to Arnaud Soirat, chef executive for copper and diamonds at Rio Tinto, increased consumption from new technologies, including electric vehicles, will drive demand for the metal and its by-products, he said.

“We anticipate global market supply and demand will keep close to balance in 2019 and 2020,” he said, noting that after that the deficit will become increasingly evident.

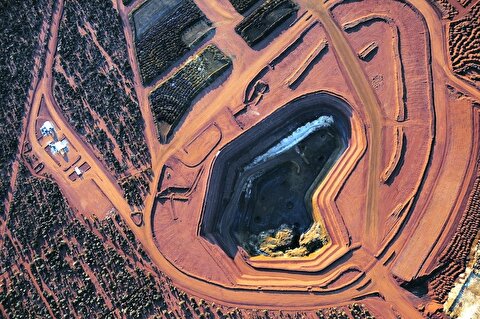

The outlook is widely shared by other experts, including CRU analyst Hamish Sampson. According to him, unless new investments arise, existing mine production will drop from 20 million tonnes to below 12 million tonnes by 2034, leading to a supply shortfall of more than 15 million tonnes.

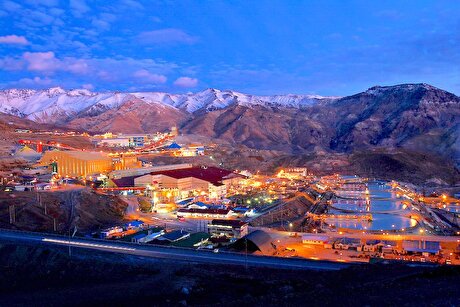

Over 200 copper mines currently in operations will reach the end of their productive life before 2035.

The situation looks even worse when considering that over 200 copper mines currently in operations will reach the end of their productive life before 2035, Sampson said on Monday.

Only if every single copper project currently in development or being studied for feasibility is brought online before then, including most discoveries that have not yet reached the evaluation stage, the market could meet projected demand, the consultant said.

Colin Hamilton, managing director of commodities research at BMO Capital Markets, fully agrees with Sampson. He told MINING.com on Tuesday that even when there was an apparent rise in copper inventories on exchanges around the world, which somehow has dented confidence in the metal, the outlook is very positive.

“What we’ve seen is a shift from invisible to visible stockpiles,” Hamilton said, adding that Chinese inventories so far this year are at the lowest levels in recent times.

Delivery to exchanges, however, does weigh on prices because of data-driven investors, which adds to the facts that shareholders are still somewhat opposed to companies investing in new projects and exploration. “They just want returns,” Hamilton said.

He believes the expected copper supply crunch will become “much more real” in 2019, due to the lack of mega-projects coming on stream before the mid-2020s and as global production will peak by the second half of next year.

Newmont nets $100M payment related Akyem mine sale

First Quantum scores $1B streaming deal with Royal Gold

Caterpillar sees US tariff hit of up to $1.5 billion this year

Gold price rebounds nearly 2% on US payrolls data

Copper price collapses by 20% as US excludes refined metal from tariffs

St Augustine PFS confirms ‘world-class’ potential of Kingking project with $4.2B value

B2Gold gets Mali nod to start underground mining at Fekola

Goldman told clients to go long copper a day before price plunge

Copper price posts second weekly drop after Trump’s tariff surprise

Codelco seeks restart at Chilean copper mine after collapse

US slaps tariffs on 1-kg, 100-oz gold bars: Financial Times

BHP, Vale offer $1.4 billion settlement in UK lawsuit over Brazil dam disaster, FT reports

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

SAIL Bhilai Steel relies on Danieli proprietary technology to expand plate mill portfolio to higher steel grades

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

Australia weighs price floor for critical minerals, boosting rare earth miners

Australia pledges $87M to rescue Trafigura’s Nyrstar smelters in critical minerals push

Fresnillo lifts gold forecast on strong first-half surge

US slaps tariffs on 1-kg, 100-oz gold bars: Financial Times

BHP, Vale offer $1.4 billion settlement in UK lawsuit over Brazil dam disaster, FT reports

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

SAIL Bhilai Steel relies on Danieli proprietary technology to expand plate mill portfolio to higher steel grades

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

Australia weighs price floor for critical minerals, boosting rare earth miners

Australia pledges $87M to rescue Trafigura’s Nyrstar smelters in critical minerals push

Fresnillo lifts gold forecast on strong first-half surge