China’s imports are reshaping the global aluminum market

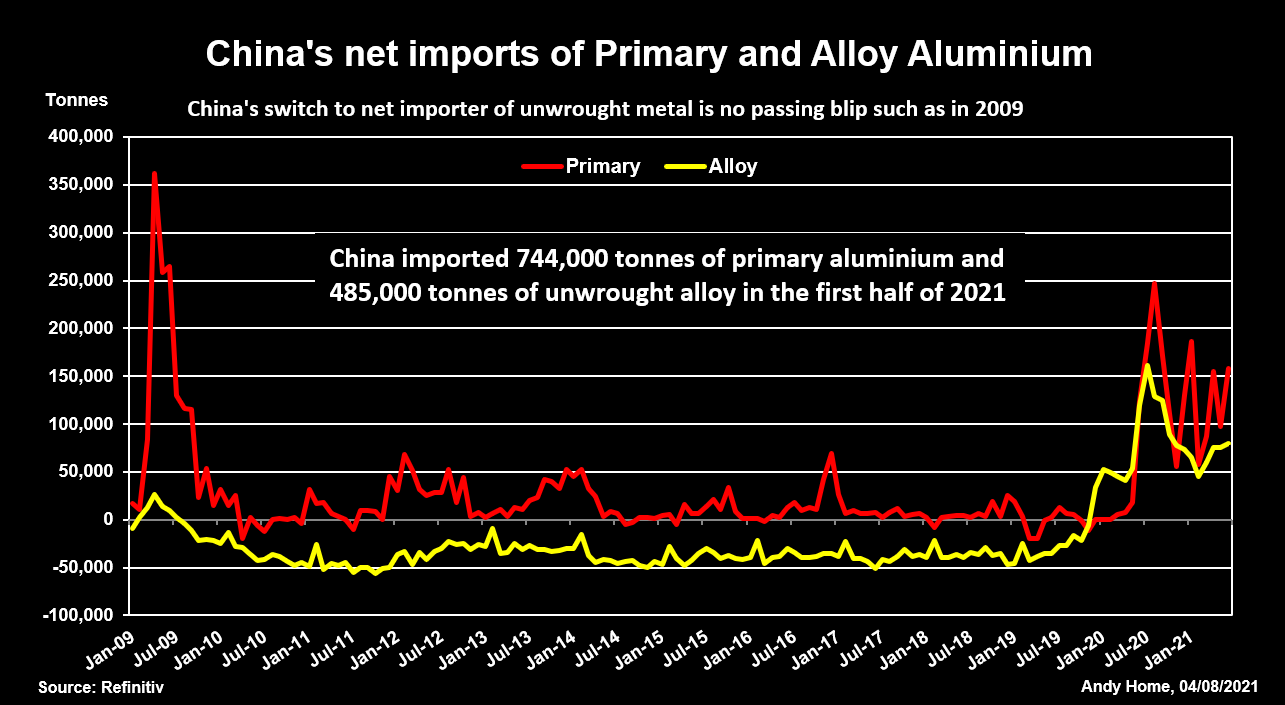

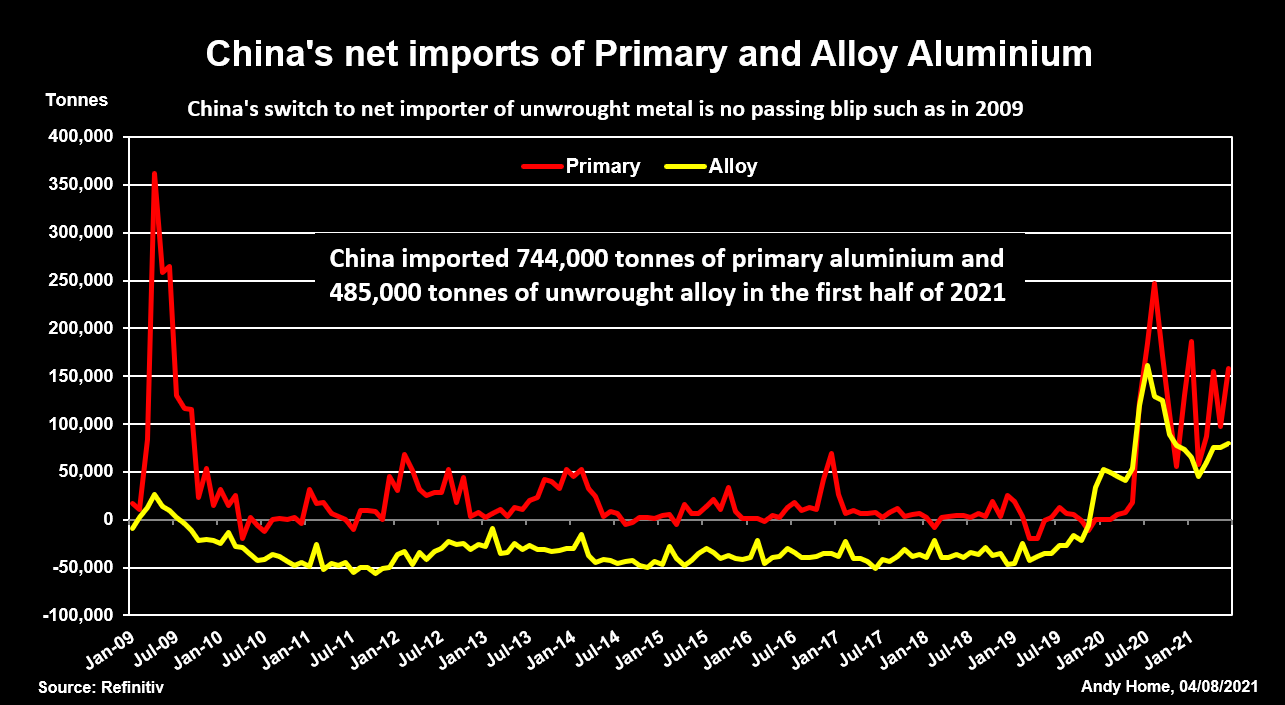

When the world’s largest producer started tapping the international marketplace early last year, it appeared to be a temporary blip caused by China’s rapid bounce-back from lockdown.

A year on, however, and it’s becoming clear that this is no fleeting phenomenon such as seen during the financial crisis a decade ago.

China’s primary metal production growth has stalled as power-hungry smelters adapt to tightening energy efficiency targets. Producers can’t keep pace with demand, meaning imports are needed to rebalance the domestic market.

This is exerting a huge gravitational pull on aluminum stocks as accessible metal migrates to Asian locations to capitalize on China’s new import appetite.

Aluminum buyers everywhere else, particularly in the United States, are paying the price in the form of record-high physical premiums.

A structural shift

China has hoovered up 1.8 million tonnes of primary aluminum since these accelerated imports began in the second quarter of 2020.

That exceeds the 1.5 million tonnes imported in 2009, the only historical precedent for such elevated volumes. However, back then the surge washed out after six months. The current import wave has lasted over a year.

Moreover, a simultaneous shift from net exporter to net importer of unwrought alloy is a new development and one which seems due to the partial off-shoring of China’s scrap-alloy processing chain.

It’s noticeable that the relaxation of a ban on imports of scrap metal at the end of last year hasn’t generated any increased flow of aluminum recyclables. Copper scrap imports leaped by 91% in the first six months of this year, but those of aluminum were up by just 5% on last year’s low levels.

China’s proposed ban on scrap imports has displaced global flows to Malaysia and India, which are now the two largest-volume suppliers of alloy to the Chinese market.

If the displacement is permanent, higher alloy imports are here to stay.

The big question is whether primary metal imports are also going to become the new normal.

The tightness in China’s domestic market is currently being accentuated by logistics – many smelters are in the northwest, far from consumption hubs in the east – and rising export demand for products as recovery takes hold in the rest of the world.

But the power constraints facing a still largely coal-dependent aluminum smelter sector aren’t going to go away as energy efficiency targets tighten.

The market is betting that the country will continue to struggle to meet downstream demand from product manufacturers.

This is why the Shanghai aluminum price continues to hover near May’s decade highs and the London Metal Exchange (LME) price is sitting pretty at $2,580 per tonne, just below last week’s three-year high of $2,642 per tonne.

Stocks on the move

China’s evident supply-chain stress is not just driving outright prices higher.

It’s also feeding into the explosive rise in physical premiums everywhere else. U.S. buyers are already paying in excess of $3,000 per tonne for their metal with the premium for Midwest delivery hitting an unprecedented $750 per tonne over the LME cash price.

A ferocious rebound in aluminum demand – up 18% in the first five months of this year, according to the Aluminum Association – has left the US market short of metal.

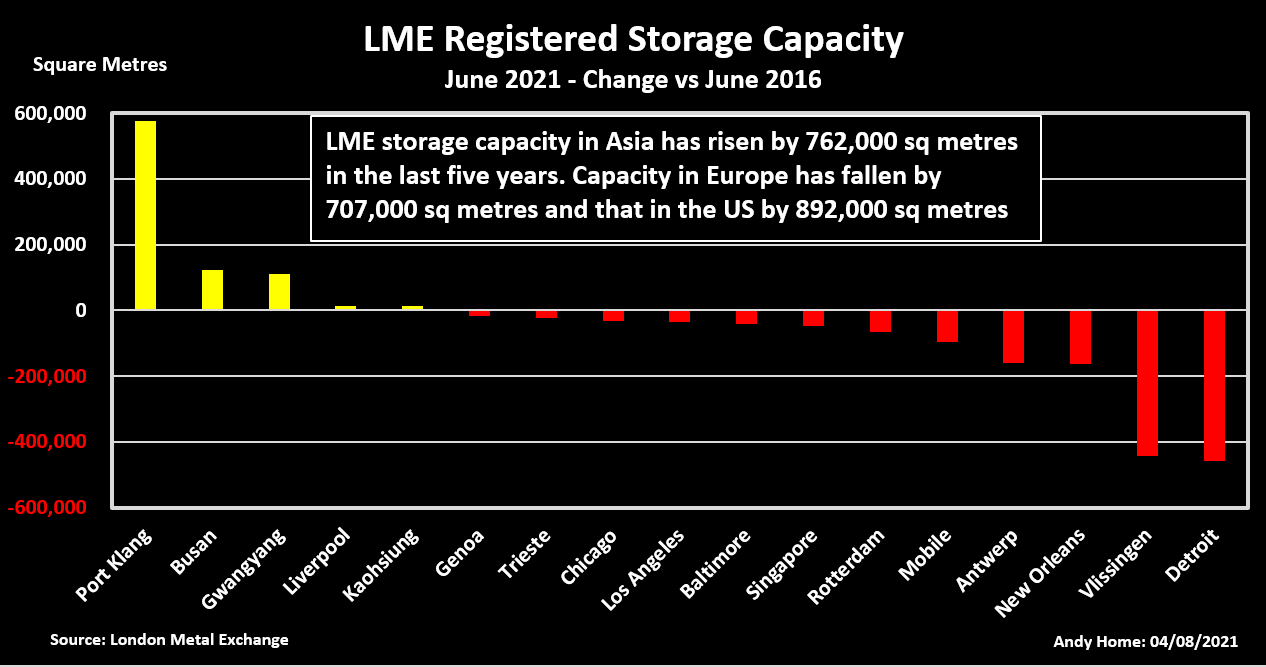

A dysfunctional freight sector isn’t helping but the underlying issue facing both U.S. and European buyers is that most of the LME’s stocks are in Asia.

The surplus metal resulting from the financial crisis accumulated in Detroit and then the Dutch port of Vlissingen.

This time around the world’s covid-19 surplus is sitting at Asian locations within easy shipping distance of China, particularly Malaysia’s Port Klang.

The port accounts for 61% of total LME aluminum inventory and Asian locations cumulatively 90%. As of the end of May, 85% of the 870,000 tonnes of metal sitting in off-warrant storage were also in Asia.

Port Klang is now the single largest hub of exchange-approved warehousing capacity, overtaking Rotterdam in the last year to reach 770,000 square metres at the end of June.

LME storage capacity has shrunk over the last five years but not in Asia and that’s largely to do with the redistribution of aluminum inventory, far more of which is stored in the exchange’s warehouse network than any other metal.

LME stocks may not be a perfect reflection of the distribution of fully off-market stocks, but high physical premiums on both sides of the Atlantic suggest there is little immediately available inventory to fill in supply-chain gaps.

Rebalancing the Chinese market

There is no shortage of drivers at work in high physical premiums but the competition for accessible stocks with China is obviously aggravated by the fact those stocks are sitting a long distance from US Midwest buyers.

The rest of the world is praying for an end to the disruption that has roiled global freight but relief might yet come from Chinese policy-makers.

The sale of 140,000 tonnes of state aluminum in July seems to have had little impact either on price or supply. Shanghai Futures Exchange inventory is still sliding, with last Friday’s count of 256,214 tonnes the lowest since January.

However, China’s policymakers have another powerful lever, one that is already being used in the steel sector, where Beijing is also trying to juggle the need to reduce output while simultaneously meeting domestic demand.

Steel export tax rebates have been eliminated across a broad spectrum of products to divert export flows into the domestic market.

Aluminum product exports still qualify for a tax rebate, which is one of the reasons so much semi-manufactured product leaves the country – around 2.5 million tonnes in the first half of 2021.

Given the need to import increasing amounts of high-priced primary metal to satisfy products demand, the rebates on exports of those products are starting to look increasingly anomalous.

There may be another twist in this new Chinese aluminum narrative and another shift in a fast-changing global landscape.

Source: Mining.com

Newmont nets $100M payment related Akyem mine sale

First Quantum scores $1B streaming deal with Royal Gold

Caterpillar sees US tariff hit of up to $1.5 billion this year

Copper price collapses by 20% as US excludes refined metal from tariffs

Gold price rebounds nearly 2% on US payrolls data

St Augustine PFS confirms ‘world-class’ potential of Kingking project with $4.2B value

B2Gold gets Mali nod to start underground mining at Fekola

Copper price posts second weekly drop after Trump’s tariff surprise

Goldman told clients to go long copper a day before price plunge

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

SAIL Bhilai Steel relies on Danieli proprietary technology to expand plate mill portfolio to higher steel grades

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

Australia weighs price floor for critical minerals, boosting rare earth miners

Australia pledges $87M to rescue Trafigura’s Nyrstar smelters in critical minerals push

Fresnillo lifts gold forecast on strong first-half surge

Why did copper escape US tariffs when aluminum did not?

Fortuna rises on improved resource estimate for Senegal gold project

Caterpillar sees US tariff hit of up to $1.5 billion this year

NextSource soars on Mitsubishi Chemical offtake deal

Copper price slips as unwinding of tariff trade boosts LME stockpiles

SAIL Bhilai Steel relies on Danieli proprietary technology to expand plate mill portfolio to higher steel grades

Alba Discloses its Financial Results for the Second Quarter and H1 of 2025

Australia weighs price floor for critical minerals, boosting rare earth miners

Australia pledges $87M to rescue Trafigura’s Nyrstar smelters in critical minerals push

Fresnillo lifts gold forecast on strong first-half surge

Why did copper escape US tariffs when aluminum did not?

Fortuna rises on improved resource estimate for Senegal gold project