Panjiva Insights Old Age, Calm Waters – Economic Outlook

Q: What is the risk of an economic downturn, and are trade risks worsening it?

S&P Global Economics’ view is that the current slowdown in economic growth – likely to 2.3% this year from 2.8% last year and a drop to trend growth in 2020 – is a natural part of the age of the economic growth cycle, which is one of the oldest on record. There analysis shows the direct impact of the trade war on growth is 35 to 40 basis points of drag in terms of direct impact.

At the August update S&P Global Economics saw a 35% chance of a recession. Since then they see the calmer waters in U.S.-China trade relations as possibly reducing that risk, particularly given the putative “phase 1” trade deal – see Panjiva’s Oct. 15 report for more.

The economy has been robust so far due to continued strength in consumer spending. Financial stress among consumers is minimal. The same cannot be set for businesses though where the weaker ISM suggests business confidence – and investment – is in decline.

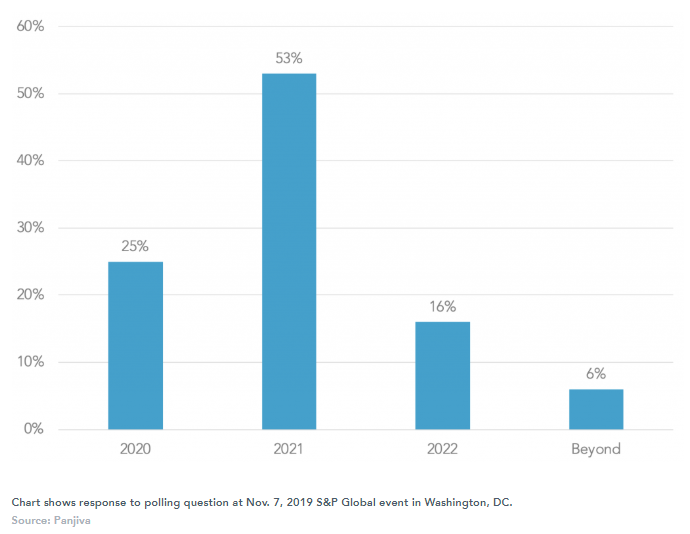

Poll: When will the U.S. enter a recession?

A poll of members of the audience – including U.S. government staff and multilateral agencies – were asked by anonymous poll when they think the U.S. will enter recession: 53% stated 2021 while 25% see a recession in 2020 and the remainder subsequently.

WHEN WILL THE U.S. ENTER A RECESSION?

Q: Is the trade war just a short- or long-term issue; is it just about tariffs or more?

The trade war as it stands has been focused on tariffs as part of the section 301 review launched by the U.S. in 2017 into Chinese intellectual property practices. As such it’s tempting to see the proposed “phase 1” deal as a one-and-done fix. In reality though there may be concerns that it could paper over deeper seated issues regarding technology development, economic development, broader economic management and attitudes towards creating “level playing fields” for global activity.

As a consequence it’s conceivable that the trade war could continue well beyond the 2020 elections and include a swathe of non-tariff measures. Those could include “unreliable entities” lists, restrictions on investments and flow of labor and so on. It’s worth noting that, ahead of the U.S. elections, several of the Democratic Party candidates are taking a more hawkish stance regarding China.

Poll: How long will the trade war between the U.S. and China last?

None of the attendees at the event expect the trade war to end by the end of 2020: phase 1 won’t be the whole answer. A conclusion during 2020 was seen as possible by 39% of respondents – slightly higher than the poll held with Commercial Banking attendees to our Oct. 31 webinar. The remainder were more-or-less evenly split in seeing a change of Presidency or an extension into the mid 2020s as a possibility.

HOW LONG WILL THE TRADE WAR BETWEEN THE U.S. AND CHINA LAST?

Q: Have the Canadian elections been a risk for passage of USMCA – will the U.S. elections or impeachment proceedings be a challenge.

S&P Global Economics believe the Canadian election result should not have an impact. All the major parties appear in favor of passing the deal, recognizing that Canada’s scale relative to the U.S. effectively make it a “policy-taker”. There may be more left-leaning policies if the Liberal Democrats under Prime Minister Trudeau pursue a coalition with the NDP, which may bring calls for more environmental protection, but not a change in USMCA (or CUSMA as it is known locally.

In the U.S., the impeachment process may increase the likelihood that the House approves the bill in order to show business-as-usual is still getting done. There is a risk, however, that significant changes in enacting legislation to support labor rule enforcement may trigger Mexico to revisit its approval for what is known locally as T-MEC. In any event there are only a few legislative days left in 2019 in the U.S.

Q: Are there any risk factors in new trade deals being signed, or are trade deals inherently “good”?

Most modern trade deals – including USMCA and Europe’s deal with Canada – include digital trade chapters to ensure consistency in rule-making. One concern though is that a lack of consistency within trade deals – or the absence of digital chapters in competing deals like RCEP – could lead to a balkanization of the internet. That in turn could restrict growth in digital trade.

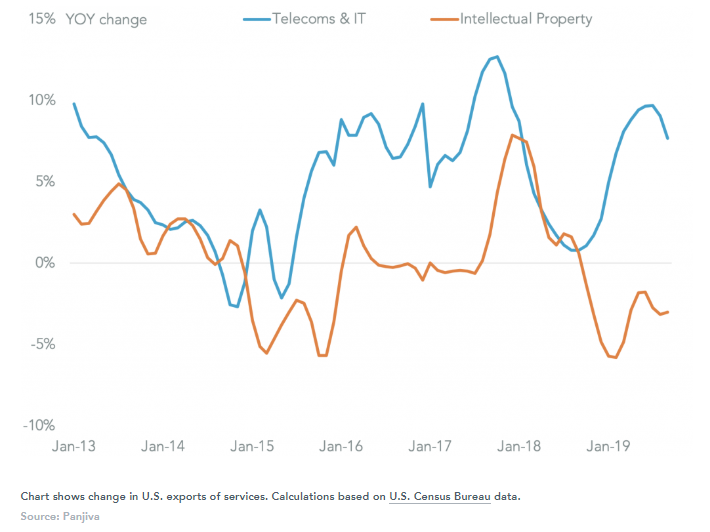

There’s also a challenge in enforcing the rules in the absence of significant government-gathered data on digital trade. U.S. published data within trade statistics consists of a single line “telecoms and IT services” within trade data published by the U.S. Census Bureau alongside a bundled line for “intellectual property”. The paucity of data may make it difficult to assess the success or otherwise of digital trade policies.

Panjiva analysis of that data shows that total U.S. exports of telecoms / IT services reached a record $3.92 billion in September after rising 7.7% on a year earlier. Intellectual Property meanwhile fell for a third month by 0.3%, and outnumbers telecoms / IT by 2.6:1.

IT SERVICES CYCLE TURNING, IP IN A PROLONGED DOWNTURN

Q: Is it just the U.S. starting trade fights, or are other countries becoming more aggressive toward the U.S.?

Generically speaking it has been the Trump administration’s preference for bilateral dealmaking, and the use of tariffs as part of that policy which has been the defining feature of global trade policy developments in the past two years. The U.S. may choose to pursue further tariff-led interventions – particularly against south-east Asian countries including Vietnam and Malaysia – if successes with China or the USMCA are not forthcoming.

There have also been some signs of other countries taking the U.S. lead of using trade policy to achieve geopolitical ends. One example has been the spat between the Japan and South Korea, while India’s use of tariffs against Pakistan are another.

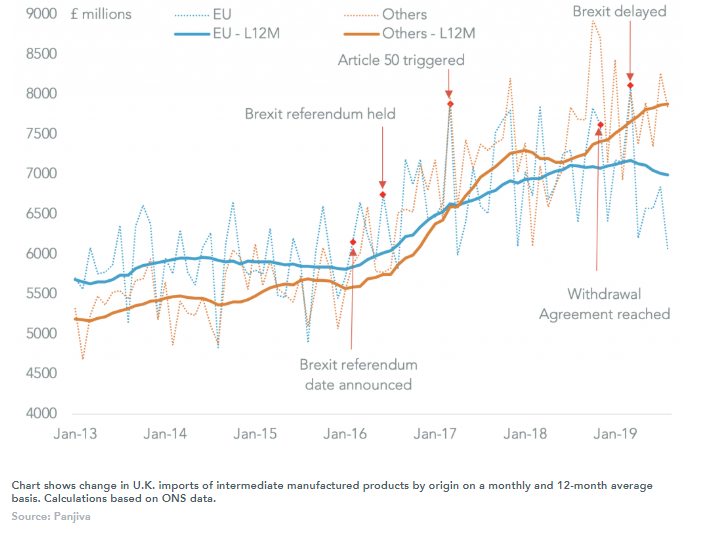

Q: Does Brexit matter in the long-term either on a stand-alone basis or for U.S. specifically?

The Brexit process – now delayed until February at the earliest – has already forced companies to rethink their supply chains. Panjiva’s analysis shows that 87.6% of all intermediate capital goods imports product lines have seen a reduction in the proportion of sourcing from the EU in the 12 months to Aug. 31 compared to 2015.

There should be minimal impact on the U.S.-economy as a whole. The U.S. is largely a domestic economy, and the U.K. is a small part of its international trade. There may be isolated significant impacts though – for example in the finance industry. Investments by U.K. companies overseas are continuing apace, as shown by investments by Jaguar Land Rover in new distribution facilities in the U.S.

Trump weighs using $2 billion in CHIPS Act funding for critical minerals

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Codelco cuts 2025 copper forecast after El Teniente mine collapse

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Abcourt readies Sleeping Giant mill to pour first gold since 2014

SQM boosts lithium supply plans as prices flick higher

Pan American locks in $2.1B takeover of MAG Silver

Nevada army depot to serve as base for first US strategic minerals stockpile

Viridis unveils 200Mt initial reserve for Brazil rare earth project

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

KoBold Metals granted lithium exploration rights in Congo

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Silver price touches $39 as market weighs rate cut outlook