Zinc sentiment staring into the bear pit

While zinc’s macro-fundamentals could arguably support more robust prices, the metal’s price has languished since its decade-high rally to $1.63 per lb. ($3,595 per tonne) in early 2018, and has struggled to break above $1.36 per lb., or $3,000 per tonne. At press time the price of the corrosion-inhibiting metal on the London Metal Exchange (LME) was in the $1.10 per lb. range ($2,420 per tonne), near its low for 2019.

Counter to zinc’s price weakness is the metric that global refined inventories have dropped to multi-decade lows. Refined zinc inventories in LME warehouses are at a reported 77,000 tonnes, while reported inventories on the Shanghai Futures Exchange are at 89,500 tonnes.

Counter to zinc’s price weakness is the metric that global refined inventories have dropped to multi-decade lows

Just how tight are inventories? Total current reported global refined inventories of 250,000 tonnes represents a week of global consumption needs, which is up slightly from lows seen earlier this year, when just five days of supply resided in the metal warehouses. However, these historically low refined inventories have not been able to add much of a catalyst to prices.

Reflective of this sentiment, the consensus long-term zinc price forecast has recently seen downgrading by many banks and brokers to the $1.00 to $1.10 per lb. range.

Global trade war rhetoric over the past year, specifically between the U.S. and China, has cast a pall on most commodities and materials with muted demand, limited industrial growth expectations and lower raw material consumption levels, triggering expanded bearish sentiment.

This negative macroeconomic sentiment has hit Asian economies harder than most, followed by Europe.

One of the main economic barometers, China’s Manufacturing Purchasing Managers Index (PMI), measures economic activities in the Chinese manufacturing sector on a monthly basis. PMIs have posted a general negative trend since early 2018, and have come in short on numerous forecasts over the past year. With a drop to 49.4 in June, PMIs have come in below 50 for four out of the last six months this year. The 50-point level separates expansion on the upside from contraction downwards. July’s forecast China PMI is 49.6.

Amongst the base metals, zinc specifically has recently underperformed its sister metals, having dropped as much as 35% off its early-2018 highs. Copper and nickel have seen drops of up to 20% and 31%.

“The zinc market bull run is nearing an end,” Orest Wowkodaw, managing director and senior research analyst at Scotia Capita, says in a July 11 research note. “Although visible zinc stocks have finally reached critically low levels, as predicted, the negative macroeconomic sentiment overhang has served to largely ruin the party.”

Zinc ingots. Credit: Glencore.

The closure of three global marquee mines (Lisheen in Ireland, Brunswick in Canada and Century in Australia) between 2013 and 2016, as well as production cuts at some of Glencore’s (LON: GLEN) mines in 2016, precipitated significant tightness in the zinc concentrate supply market, and was the main catalyst of the metal’s 2016 to 2018 bull run. However, this has recently waned, with increasing concentrate supply coming online in 2018, as well as mine output growth anticipated over the next few years. This supply boost could erode the deficits and tip the balance of refined metal back into a surplus scenario this year.

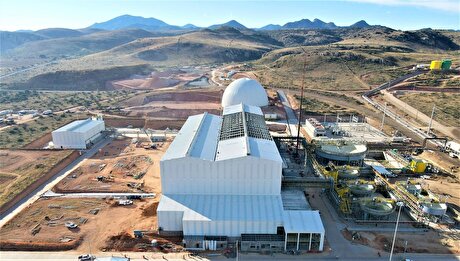

According to TD Securities’ recent “Q2/2019 Preview Equity Research note,” zinc mine supply is increasing. “With a backdrop of weaker refined demand, mine supply growth has been increasing, with several large mines entering production, including Gamsberg (in South Africa) and Dugald River (in Australia),” the bank stated. “The restart of the Century operation (also in Australia) via reprocessing of mine tailings is also adding to supply. Wood Mackenzie is projecting year-over-year mine supply growth of 3.2% in 2019, and 6.7% in 2020. We expect that mine supply growth could turn negative by 2023, with lower prices disincentivizing new projects.”

Additionally, despite more than a decade of strong year-over-year Chinese mine production growth, output dipped from 2016 to 2018 due to more stringent environmental controls. But sentiment now leans back towards incremental production increases from Chinese mines. China is the world’s largest zinc miner, at a third of global supply. Scotiabank’s recent fundamental review of major commodities assumes 2.5%-per-year Chinese mine supply growth from 2019 to 2021.

Turning zinc concentrate from the mines into refined, industry-ready zinc falls on the smelters. While there was surplus global smelting capacity over most of the past several years, more environmental regulations in China over the past couple of years has contracted their capacity and muted refined output, although some modest growth is now modelled. This incremental increase in Chinese refining capacity, plus minor anticipated increases in Western capacity, could help push the refined zinc market into surplus over the next year.

Despite these modest smelter capacity increases, treatment charges (TC) charged by the smelters to the miners to refine their concentrate have gotten higher. Negotiated annually between the smelters and zinc producers, International Benchmark TCs rose from a multi-year low of $147 per tonne of zinc concentrate in 2018 to about $245 per tonne for 2019. Even more dramatic is the soaring increase in the spot TC market that has rallied from a low of $19 per tonne in early 2018 to a high of $275 per tonne earlier this year.

Unfortunately for miners, increasing concentrate supply has swung the advantage in favour of the smelters.

Worldwide zinc consumption averages about 14 million tonnes annually. Urbanization and industrialization drive global zinc consumption, with construction, transportation and infrastructure the major sectors accounting for its use.

Zinc is primarily used for its anti-corrosion ability, acting as a sacrificial metal to inhibit rusting of steel. This galvanizing accounts for 60% of global use of the metal. Other main uses include die-casting alloys, brass production, and oxides and chemicals.

According to Scotiabank research, global zinc demand averaged 2.3% growth annually from 2012 to 2017, but saw negative 0.3% growth in 2018. The bank also forecasts negative demand growth of 0.5% this year, followed by modestly increasing consumption of 1% in 2020, and 1.5% in 2021.

While galvanizing is expected to remain by far zinc’s primary end use, potential sources for demand include agriculture. The International Zinc Association is a strong proponent of the Zinc Nutrient Initiative and Zinc Saves Kids (along with UNICEF) that has worked to advocate and implement zinc’s use as a micro-nutrient in fertilizers.

The Zinc Nutrient Initiative has started more than 500 trials in eight countries — China, India, Bangladesh, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Malawi, Brazil, Peru and Mexico — where agricultural soils are identified as zinc deficient. Adding zinc to fertilizers has evidenced significant increases in crop yields, as well as boosting nutritional value of the grown product.

Zinc battery technology is another emerging use of the metal that could see future growth. However, it remains early stage, and the battery market can be quite dynamic. Zinc air battery technology has entered commercial application and looks to offer low-cost, recharge options for grid energy storage.

Mostly mined as a primary commodity, the zinc mining space is dominated by a few, large integrated mining companies: namely Glencore, Hindustan Zinc–Vedanta and Teck, which combined represent over 20% of global mine supply.

Other top zinc producers include Nexa Resources (TSX: NEXA), Boliden, Sumitomo, Minera Volcan, Trevali Mining (TSX: TV) and Lundin Mining (TSX: LUN).

— Steve Stakiw is a geologist and former Western editor for The Northern Miner. Most recently, he has spent over 10 years in a senior role with a zinc-focused, base metals producer with operations on three continents.

Trump weighs using $2 billion in CHIPS Act funding for critical minerals

Electra converts debt, launches $30M raise to jumpstart stalled cobalt refinery

Codelco cuts 2025 copper forecast after El Teniente mine collapse

Barrick’s Reko Diq in line for $410M ADB backing

Abcourt readies Sleeping Giant mill to pour first gold since 2014

SQM boosts lithium supply plans as prices flick higher

Nevada army depot to serve as base for first US strategic minerals stockpile

Pan American locks in $2.1B takeover of MAG Silver

Viridis unveils 200Mt initial reserve for Brazil rare earth project

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

KoBold Metals granted lithium exploration rights in Congo

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Kyrgyzstan kicks off underground gold mining at Kumtor

Freeport Indonesia to wrap up Gresik plant repairs by early September

Energy Fuels soars on Vulcan Elements partnership

Northern Dynasty sticks to proposal in battle to lift Pebble mine veto

Giustra-backed mining firm teams up with informal miners in Colombia

Critical Metals signs agreement to supply rare earth to US government-funded facility

China extends rare earth controls to imported material

Galan Lithium proceeds with $13M financing for Argentina project

Silver price touches $39 as market weighs rate cut outlook